Recent progress in enhancement of physical properties of organic phase change materials and optimization of coupling thermal management of batteries

-

摘要: 为满足电动汽车锂离子电池热管理需求,具有优良温控效果的相变材料(PCM)冷却逐渐成为研究热点。本文从有机PCM物性不足出发,概括了目前复合有机PCM的制备及改进方向:添加多维高导热材料(如碳材料、纳米金属、泡沫金属等)强化导热;添加共聚物(如聚乙烯、热塑性弹性体等)提高材料柔韧性和添加阻燃剂(如红磷、聚磷酸铵等)提高阻燃效果以改善其实用性。分别指出膨胀石墨、苯乙烯-乙烯-丁二烯-苯乙烯和复合使用红磷与聚磷酸铵对导热、柔性和阻燃的显著提升。同时描述了有机PCM与热管、液冷、空冷等散热方式耦合后系统强化换热的效果,总结耦合热管时需要考虑不同热管排布;耦合液冷或空冷需要设计合适流道增强换热。随后介绍了通过模拟仿真分析有机PCM用于电池热管理系统影响因素及最佳使用工况的研究。最后总结有机PCM用于电池热管理的进展及不足,其难点仍在于其可燃和导电性的改善以及柔性有机PCM在室温下柔韧性不足,有机PCM耦合传统散热系统的车载可靠性和循环可行性也缺乏相应探讨,并为今后有机PCM用于电池热管理提出一定建议。Abstract: To meet the demand for thermal management of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicle, the cooling method with phase change materials (PCM) on battery modules has gradually become a research hotspot. Based on the poor physical properties of organic PCM, the preparation and improvement directions of composite organic PCM for battery thermal management (BTM) are summarized, including adding multi-dimensional materials such as carbon materials, nano-metals and metal foams to enhance the heat transfer, and adding copolymer such as polyethylene and thermoplastic elastomer to improve the flexibilities. Additionally, flame retardants such as red phosphorus and ammonium polyphosphate are used to improve the flame retardance for better practicabilities. Among them, expanded graphite, styrene-ethylene-butadiene-styrene, and the composite of red phosphorus and ammonium polyphosphate significantly improve the thermal conductivity, flexibility and flame retardancy respectively. Subsequently, the heat transfer enhancement effects of the system after coupling organic PCM with heat pipe, liquid cooling or air cooling are evaluated, indicating that various arrangements of heat pipe and appropriate flow channels of air and liquid should be considered. Then the optimal operating conditions of organic PCM used in BTM system is determined with numerical calculation. Finally, the progress and shortcomings of organic PCM used in BTM are summarized. It is pointed out that the difficulties of composite organic PCM used in BTM are still accounted for the improvement of flammability and conductivity and the insufficient flexibility of flexible organic PCM at room temperature. Furthermore, the reliability and cycle feasibility of PCM and traditional heat dissipation system in the process of vehicle use are still lack of verification. Totally, several suggestions are put forward for the application of organic PCM in BTM in the future.

-

化石燃料紧缺、油价上涨和燃烧过程产生的大量含氮、硫化合物愈发成为传统汽车行业发展的掣肘因素。基于能源环境的综合考虑,不少国家诸如挪威、荷兰等预计于2025~2050年逐步停产燃油汽车[1]。在此形势下新能源汽车产业发展迅速、技术鼎新,拥有着巨大发展前景。而作为电动车核心组件的锂离子电池由于决定整车性能,其高温耗损已然成为电动车产业化的一大难题。已有文献给出了车载锂电池的适宜工作温度为20~40℃,并且工作时整体温差需小于5℃[2-3],过高的温度可能造成电池热失控(TR)而自燃[4]。同时大温差下单体电池的损耗使整体串联电池组功率大幅下降,加速了电池报废[5],因此研究锂电池有效温控意义巨大。

目前的电池热管理(BTM)主要分为主动冷却式和被动冷却式两种类型[6]。主动冷却式指通过空气、水等传热介质循环以带走热量。如Chen等[7]将电池组以4×4正排布置并优化空气间隙,主动式空气冷却使得电池表面温度在50℃以下,电池表面较低的温度场延长模块循环寿命可达600%。Yuksel等[8]利用空气横向扫掠错排的电池组阵列,证明空气冷却可以将电池寿命延长一倍以上,但空气的对流换热量远不及液冷。Lan等[9]设计了一种铝微通道冷板,均匀布置在电池侧壁,2 C放电倍率下电池最高温度/最大温差仅有28.2/1.2℃。Shang等[10]将电池组布置于液体冷却板之上并在接触面增加导热垫强化换热,通过正交实验确定最优入口流速为0.21 kg·s−1,入口温度为18℃,此时最高温度和温差分别下降12.6%和20.8%。而目前大部分商用电动汽车的电池组设计如雪佛兰Blot、宝马i3、特斯拉S型均为此类结构,除去密闭性要求的高额维护外,电池放电时上方热量累积,极易造成电池组的局部温差[11]。被动冷却式散热利用热管、相变材料(PCM)等散热元件或材料实现热量交换。Liu等[12]使用板式微通道热管进行电池热管理,蒸发端与电池壁紧贴,冷凝端外加肋片强化对流,热管水平布置,2 C放电倍率下系统最高温降低7.1℃,最大温差小于5℃。Rao等[13]研究发现,功率30 W以下的锂电池使用平板热管辅助散热后,表面最高温低至50℃,最大温差低至5℃。但热管散热使用的低热导率工质如水、乙酮、丙酮等在高放电倍率下散热效果不足[14],单独使用难以满足热管理需求。而PCM是通过相态转换来对热量进行吸收或释放的材料,其系统结构无额外功率组件、在电池组蓄/放热过程中温控效果优异,基于PCM在被动式BTM领域的巨大应用前景,常被用作单独BTM,或与空冷、液冷、热管中的一种或多种耦合,提升热管理性能,优化温控策略。

相变材料通常分为固-气、液-气、固-固和固-液类PCM[15]。其中固-气、液-气两相材料相变过程中的体积变化大,难以应用于BTM系统,固-固PCM以聚氨酯、交联聚乙烯和聚合物为主[16],无毒无腐蚀但存在的问题是固相间转变的潜热值较低[17],定型复合PCM相变后虽无融化流动但微观上仍有PCM液化故本文认定属固-液相变。固-液PCM由于相变体积变化少、相变温度范围广、蓄热密度高等优势而得到了广泛应用[18]。同时因为无机PCM的相分离和过冷特性[19],在循环使用过程中稳定性较差,因此本文主要讨论有机固-液PCM及其在BTM系统中的研究现状。基于商业可行性考量,指出有机固-液PCM用于BTM仍需要解决其不足之处:首先,有机固-液PCM自身热导率并不高,如表1所示。

表 1 部分用于电池热管理(BTM)的有机固-液相变材料(PCM)热物性Table 1. Thermo-physical properties of organic solid-liquid phase change materials (PCM) for battery thermal management (BTM)PCM Thermal conductivity/(W·m−1·K−1) Latent heat/(kJ·kg−1) Phase change temperature/

℃Ref. Paraffin(PW) 0.2 255 41-44/— [20] PW 0.22 300 36/— [21] PW 0.21 200 40/— [22] Lauric acid 0.15 177 43/— [23] Myristic acid — 187 53.7/— [23] Palmitic acid 0.17 186 62.3/— [23] Stearic acid 0.17 203 70.7/— [23] Capric acid 0.15 152.7 28.9/31.9 [24] Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 600 — 146 20-25 [23] PEG 1000 0.29 142/— 35.9/29.9 [25] PEG 1500 0.31 163.4/— 48.9/42.9 [25] PEG 3400 — 171.6 56.4 [23] Tetradecanol — 205 38 [26] 1-dodecanol — 200 26 [26] 以石蜡(PW)为例,相比于脂肪酸和多元醇,拥有相对更高的潜热、合适的相变点和低廉的价格而适用于电池热管理,其热导率虽然随碳原子数有所不同,但均小于0.27 W·m−1·K−1[20-21, 27]。其次,PCM作为电池外部填充材料,相变吸热的工作特性要求其与电池紧密接触利于传热,极可能发生受外力撞击时破环电池结构,致使电池失效或短路自燃的可能。避免此类电池失效或热失控需要提高PCM力学柔韧性,较高柔韧性减少与电池接触热阻的同时可有效保护电池。另外,有机PCM大多可燃甚至易燃,在电池TR发生时会急剧加速热扩散引发重大事故,因此对有机PCM的强化阻燃十分关键。

本文集中讨论了有机PCM实用化不足之处,总结了近年来学者们的改进方向,包括从热物性角度提高热导率、力学角度提高柔韧度、化学角度提高阻燃能力对PCM改善以实现BTM运用,并针对PCM散热的局限介绍了热管、液冷、空冷与PCM的耦合系统的强化换热应用,仿真模拟对实验的延拓,为PCM在BTM中进一步发展使用提供参考和合理建议。

1. 有机相变材料及实用物性改进

1.1 有机相变材料的导热强化

热导率提高的主流方法是与高导热材料复合形成内部传热网络,传统方式为物理共混,有碳材料如膨胀石墨(EG)[28]、石墨烯(Graphene)[29]、碳纳米管(CNTs)[15],纳米金属颗粒如铝粉[30]、铜粉[31]或陶瓷填料如氮化硼(BN)[32]、氮化铝(AlN)[33]、碳化硅(SiC)[34]。用高导热骨架对PCM进行吸附是另一有效策略。常用材料有泡沫石墨[35]、泡沫金属[36]、氧化石墨烯(GO)[37]、化学改性后的多孔碳骨架[38]等。

刘臣臻等[28]将EG与PW复合压制后应用于BTM,测得EG含量为20wt%时复合PCM热导率达12.35 W·m−1·K−1,相比于纯PW提高52倍。Wang等[39]通过改性CNTs强化聚乙二醇2000 (PEG 2000)传热,添加量为5.16wt%时复合PCM热导率为0.464 W·m−1·K−1,提升了55.7% ,并且经过100次DSC循环后热物性几乎不变。Li等[32]探究了六方氮化硼(h-BN)比例和粒径对复合PCM热导率的影响,直径30 µm和40 µm的h-BN以1∶1的质量比例加入PW、高密度聚乙烯(HDPE)和硅藻土(DM)的混合物时热导率最大,可达2.498 W·m−1·K−1,相比于纯PW提高了11.49倍。He等[36]构建了以泡沫铜为导热骨架、PW为PCM并加入碳材料EG和环氧树脂(ER)的新型复合材料,EG的吸附和环氧树脂的进一步封装有效减少了PCM的泄露,热导率达2.9 W·m−1·K−1,是一种热物性优异的热管理材料。

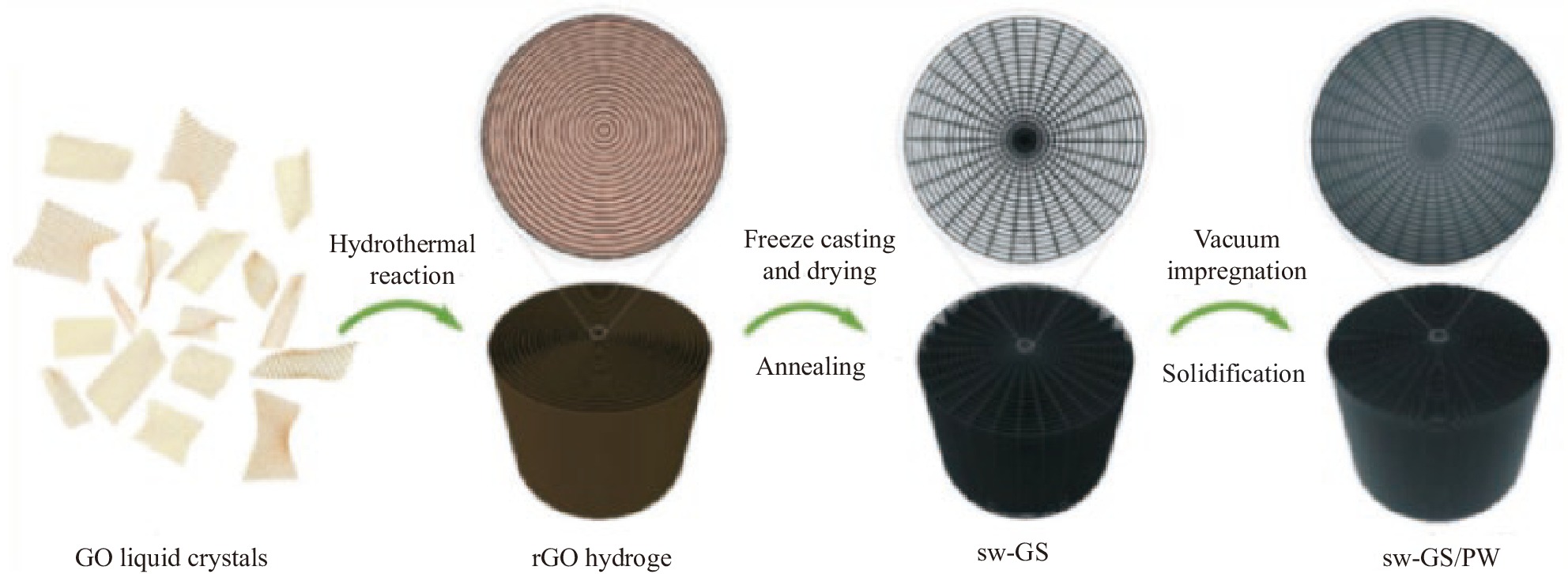

Lin等[37]利用GO以图1流程制备了蛛网结构的三维石墨烯骨架(sw-GS),真空浸渍PW后轴向、横向热导率为2.58 W·m−1·K−1、1.78 W·m−1·K−1,分别提高约1260%和840%,经过100次熔化/凝固循环后热物性基本不变。Atinafu 等[38]用金属-有机框架材料(MOF)合成氮掺杂多孔碳骨架(NPC-Al)吸附PEG 2000,其吸附填充率达85%,具有0.41 W·m−1·K−1的热导率且稳定性有显著提高,50次DSC循环后保持率达99.5%。

表2对复合PCM的热导率提高进行了综述,不同材料由于与PCM间界面热阻不同,造成不同程度声子散射而对热导率提升效果差异较大。纳米颗粒和陶瓷填料由于团聚,对热导率的提升幅度有限,以h-BN为例,在20wt%的高添加比例下仅有0.85 W·m−1·K−1,20wt%的纳米铝、纳米TiO2提升幅度仅为216%、76%。GO类骨架和多孔碳骨架对热导率的提升并不显著(热导率通常小于2 W·m−1·K−1),但其多孔结构对PCM的吸附使得整体热稳定性较高,DSC循环后相变焓保有90%以上。对热导率提升最有效的方法是共混EG或使用泡沫金属吸附。物理共混高导热填料除其自身高热导率外,形成的导热通道加速声子扩散,而EG由于高比表面积[40],共混后的复合PCM热导率远高于同比例的多壁碳纳米管(MWCNT)、CNT、石墨烯[30],20wt%EG的复合PCM热导率可达12.4 W·m−1·K−1。泡沫金属通过其本身孔隙网络为声子扩散提供路径,其路径上的强混合扰动也破坏了热流边界层进一步强化传热[41]。可是,如泡沫铜在加快热扩散同时吸附PCM,提升热导率在10倍以上,但受限于尺寸无法满足不同电池结构,因此EG是目前BTM用有机PCM提高热导率的主流选择。

表 2 BTM用有机PCM热导率强化及其热物性Table 2. Thermal conductivity enhancements and thermo-physical properties of organic PCM for BTMPCM and

additivesMass fraction Thermal conductivity

of pure PCM/

(W·m−1·K−1)Thermal conductivity of

composite PCM/

(W·m−1·K−1)Phase change

temperature/

℃Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Ref. EG/PW 20∶80 0.15 1.90 — — [29] GNP/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.87 — — [29] CNT/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.37 — — [29] Graphene/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.49 — — [29] Nano-Al/PW 20∶80 0.25 0.78 53.89/49.46 282.50/281.20 [30] Nano-TiO2/PW 20∶80 0.25 0.43 54.28/50.74 283.09/280.64 [30] AlN/EG/ER/PW 20∶3∶27∶50 0.20 4.33 47.20/— 116.30 [33] EG/ER/copper foam/PW — 0.23 2.90 49.80/— 75.00 [36] sw-GS/PW 2.25∶97.75 0.19 2.58 53.50/45.40 172.50/158.90 [37] NPC-Al/PEG 2000 15∶85 0.27 0.41 54.40/— 155.30/— [38] CNT/MOFs/PEG 2000 5.16∶24.84∶70 0.30 0.46 52.40/27.40 96.20/90.10 [39] MWCNT/graphene/PW 0.3∶0.7∶99 0.39 0.87 45.30/40.80 203.80/198.00 [40] EG/PW 10∶90 0.28 6.4 39.50 187.88 [42] CNT/PW 10∶90 0.28 0.39 40.30 172.62 [42] h-BN/Na2SiO3/PW 18∶0.9∶81.1 0.12 0.85 52.30/47.90 165.40/176.10 [43] EG/aluminum foam/graphene/PW — 0.20 7.1 — — [44] NPC/myristic acid-stearic acid 12∶26.4∶61.6 0.17 0.37 49.45/— 164.33/— [45] EG/SiO2/low-density polyethylene/RT 45 7∶5.5∶30∶57.5 — 3.30 44.00 77.80 [46] Notes: EG—Expanded graphite; GNP—Graphene nanosheets; CNT—Carbon nanotubes; ER—Epoxy resin; MWCNT—Multi-walled carbon nanotubes; NPC—N-doped porous carbons; RT 45—Rubitherm 45. 1.2 有机相变材料的柔性改进

向PCM材料中通过浸渍或物理共混添加共聚物可以有效提高PCM柔韧性和改善其熔融易渗漏的不足。研究较多的传统共聚物材料有低密度聚乙烯(LDPE)、高密度聚乙烯(HDPE)、环氧树脂(ER)等[47],形成支撑骨架可以改善PCM塑性和熔融易渗漏的不足,但其形变稳定性仍相对不足。因此具有更优异弹性和柔韧性的新型多元共聚物如热塑性酯弹性体(TPEE)[47]、烯烃嵌段共聚物(OBC)[48]、乙烯-醋酸乙烯酯(EVA)[49]、苯乙烯-丁烯-丙烯-苯乙烯(SEPS)[50]、苯乙烯-丁二烯-苯乙烯(SBS)[51]、苯乙烯-乙烯-丁二烯-苯乙烯(SEBS)[52]、三元乙丙橡胶(EPDM)[53]等被提出用于进一步改善更宽温度范围内的柔性。

Huang等[47]以SBS为支撑骨架、TPEE为封装材料、PW为PCM并加入EG制备了柔性复合PCM。在室温下热导率可达1.2 W·m−1·K−1且弹性韧性优异,拥有 0.09 MPa的抗拉强度,如图2所示,在60℃下可旋转720°,90℃下可拉伸至2倍。

Wu等[48]选择带有具有更高柔韧性的共聚酯热塑性弹性体(TPC-et)替代OBC,制备了一种室温甚至低温下的柔性PCM,在室温下具有1.64 W·m−1·K−1的热导率和在−110~25℃都优于OBC柔性PCM的抗拉、抗弯、抗压强度。Li等[49]以PW为PCM,EVA和环己烷为载体和溶剂,所得柔性复合PCM具有 1.7 W·m−1·K−1的热导率,在30℃下抗拉、抗弯曲强度分别只有0.83 MPa、0.02 MPa。Lin 等[50]在PW与EG的复合材料中添加SEPS增强其热致柔性,导热率和相变焓分别达2.671 W·m−1·K−1 和155.4 kJ·kg−1 以上,且在外力作用下能90°弯曲。Cao 等[52]将PW、SEBS、h-BN 以6∶2∶2的质量比例在60℃共混,随后在140℃下热压10 min,所得复合柔性PCM在可50℃下拉伸和弯曲,弹性模量仅为0.72 MPa。Wu等[54]提出另一种具有热诱导柔性和形状恢复能力的复合PCM。通过在PW中加入5wt%EG和16wt% OBC所得,材料热导率为2.34 W·m−1·K−1,弹性模量为63.9 MPa,具有优异的形状恢复特性。

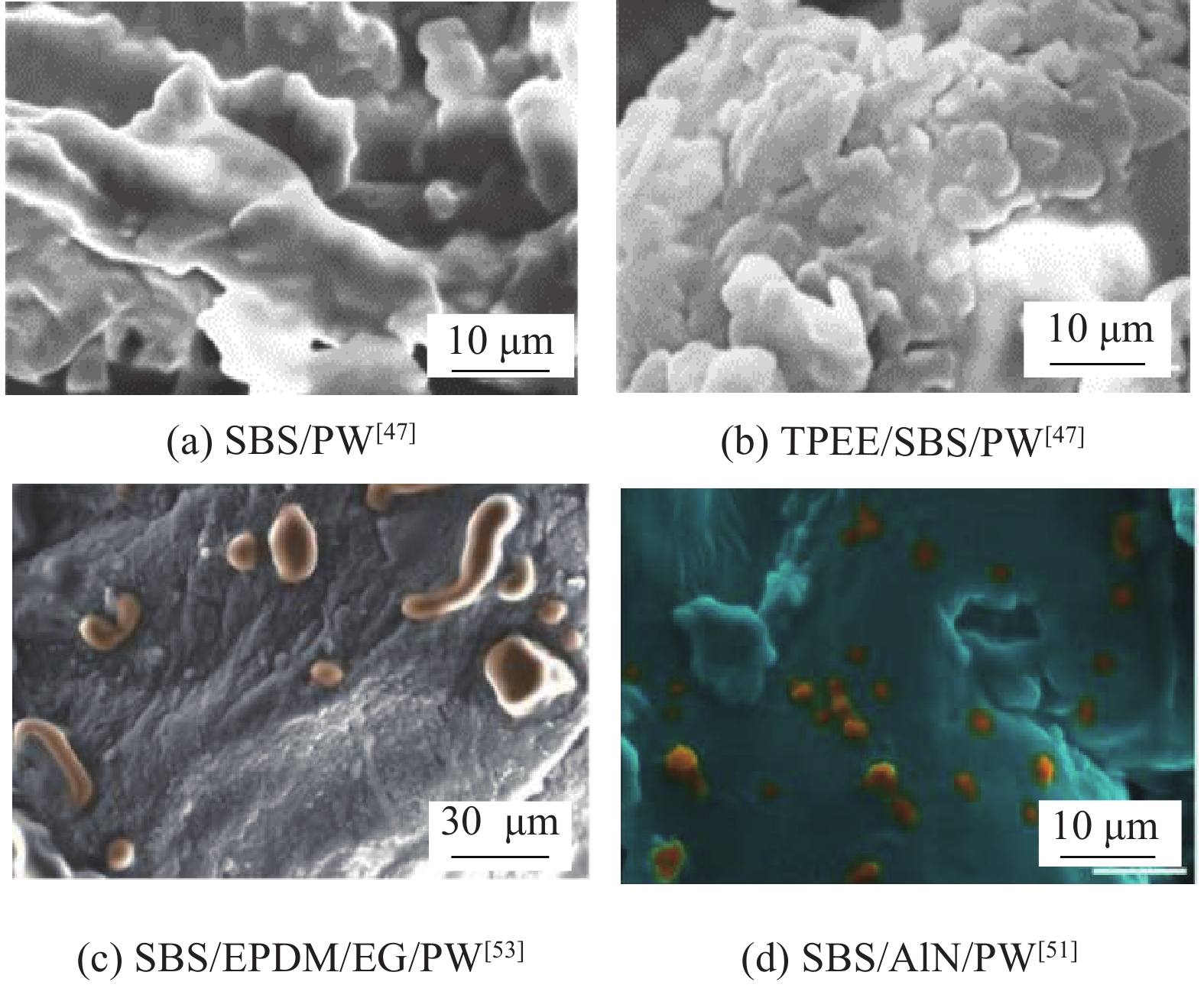

近年来对柔性PCM的研究仍相对较少。图3为部分柔性PCM的SEM图像,从微观上阐释了共聚物与PCM的混匀结合,如图3(a)、图3(b)所示共聚物在PCM表面凝聚成膜状,提高其塑性能力并对PCM进行了二次封装;图3(c)、图3(d)则可见蠕虫颗粒状共聚物的附着,PCM整体弹性拉伸能力也能得到极大改善。近年来含不同高分子聚合物的柔性PCM如表3所示,除OBC外其他共聚物的添加均使复合柔性PCM的抗拉/弯曲强度小于1 MPa,极大减小弹性模量,如SEBS复合柔性PCM弹性模量仅有0.72 MPa,这可以实现对电池的有效保护并有效贴合减少接触热阻。但大部分材料表现热致柔性,常温下柔韧性不佳,但高温环境却有悖于PCM进行热管理的初衷。同时共聚物的添加也极大影响了复合PCM的热导率及潜热值,添加比例达50wt%时,柔性PCM的热导率最高只为0.95 W·m−1·K−1,潜热仅在57.1~120 kJ·kg−1。但总体上看,作为一种新型BTM材料,柔性PCM的热致柔性和协调封装能力仍在BTM领域具有独特优势和优良的应用前景。

表 3 BTM用有机PCM柔性强化及其热物性Table 3. Flexibility enhancements and thermo-physical properties of organic PCM for BTMPCM and

additivesThermal

conductivity/

(W·m−1·K−1)Phase change

temperature/

℃Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Mechanical property Ref. Test temperature/℃ Tensile and

bending

strength/MPaModulus of

elasticity/

MPaEG/SBS/TPEE/PW(5:10:5:80) 1.20(30℃) 56.7/— 172.6/— 60 0.09/— — [47] EG/TPC-et/PW(10:45:45) 1.64 46.4/— 102.0 25 0.88/0.14 — [48] EG/OBC/PW(10:45:45) 1.57 50.1/— 101.0 25 5.44/1.21 — [48] EVA/EG/PW(47.5:5:47.5) 1.70 53.0 121.0 30 0.83/0.02 — [49] SEPS/EG/PW(9.5:5:85.5) 2.67 48.0/— 211.9 50 — — [50] SBS/AlN/PW(50:15:35) 0.50 46.8 57.1 50 0.16/0.16 67.00 [51] h-BN/SEBS/PW(20:20:60) 2.80 40.1-44.3/— 148.3 — — 0.72 [52] EG/SBS/EPDM/PW(5:12:3:80) 1.25 50.9/— 133 60 0.51/— — [53] OBC/EG/PW(19:5:76) 2.34 39.5 185.4 60 — 63.90 [54] SBS/EG/PW(60:3:57) 0.88 50.6 78.3 — 0.34/0.51 — [55] EG/SEBS/PW(5:20:80) 1.23 47.4 159.2/166.5 — — — [56] OBC/EG/eicosane(20:3:80) 1.21 33.5 170.2 — — — [57] OBC/EG/tetracosane(20:3:80) 1.18 47.4 175.1 — — — [57] HDPE/EG/eicosane(20:3:80) 1.25 33.4 169.0 — — — [57] EG/silicon rubber/h-BN/PW(3:55:5:28) 0.95 47.3/— 62.7 — 0.53/— — [58] Notes: TPC-et—Copolyester thermoplastic elastomer with polyether soft segment; OBC—Olefin block copolymer; EVA—Ethylene vinylacetate; SEPS—Styrene butene propylene styrene; SEBS—Styrene ethylene butylene styrene; HDPE—High density polyethylene. 1.3 有机相变材料的强化阻燃

阻燃效果的评价通常有两种方式[59]:一是极限氧指数(LOI),指材料在氮氧混合气体内开始燃烧时需要的氧气比例,LOI值越高代表阻燃效果越佳;另一种是燃烧时的热释放率(HRR),可以直观看出电池或材料燃烧强度。在有机PCM中混杂玻璃纤维[59]、聚磷酸铵(APP)[60]、Al(OH)3[61]、硅气凝胶[62]等阻燃剂是一种有效提高阻燃性的方式,在燃烧过程中形成致密保护层或释放不可燃气体隔绝氧气达到阻燃效果。

Niu等[60]提出了一种具有阻燃涂层的低导热相变复合材料,在PW含量为40wt%,硅气凝胶含量为60wt%时热导率最低,仅有0.051 W·m−1·K−1,在对复合PCM进行阻燃材料涂覆后,其LOI指数高达56.31%,随后的700℃ TR测试结果表明该材料的绝热性使得相邻电池模块温度仅有182.6℃。Weng 等[61]选择以丙烯酸十八酯、1, 6己二醇二丙、过氧化苯甲酰和EG合成复合PCM,并添加15wt%的Al(OH)3达到阻燃目的,在模拟实际电池TR时,HRR从242.5被降低至204.4 kW·m−2。Li等[62]利用非可燃PCM和柔性SiO2纳米纤维的协同作用制备了一种防TR材料,同时具备制冷、灭火、保温等多种功能。当TR触发时,材料除了通过相变吸热外,硅溶胶会转化为硅气凝胶纳米颗粒(热导率由3.6降低为0.026 W·m−1·K−1),进一步抑制TR。Huang等[63]将高潜热PW作为PCM,SBS作为支撑材料并添加EG和阻燃剂(APP/H3PO4/ZnO)制备了阻燃柔性复合PCM。实验结果显示,在阻燃剂含量为15wt% 时PCM在燃烧过程中形成致密碳层,阻燃效果最佳,LOI值达35.95%。此外,利用加热棒模拟了200℃下的电池TR,系统TR时峰值HRR为801 kW·m−2,远低于纯PW体系的2980 kW·m−2。

阻燃剂阻燃机制各不相同,红磷(RP)、APP受热分解均可加速材料脱水结焦形成碳层,后者的非挥发性含磷物质残余和分解过程中产生的不燃性氮气、氨气也稀释了空气含氧量实现阻燃[64]。Al(OH)3阻燃则通过受热分解成能汽化吸热的水和具有成膜能力的Al2O3阻碍传热传质过程[61]。因此,从阻燃机制出发寻找低比例下高效阻燃效果的阻燃剂,改善阻燃剂与PCM的共混导致的潜热下降仍是学者所关注重点。不同的阻燃剂和复合PCM的阻燃效果总结如表4所示,LOI指数达26%~56.3%,峰值HRR均有不同程度下降。图4对其进行了直观对比,TR时热量释放明显减少,下降比例在15.2%~73.1%,复合使用APP与RP,其协同阻燃效果提升明显。虽然峰值HRR最低控制可在190.3 kW·m−2内,TR峰值温度仍处于364~764℃的高温区域,导致人员伤亡和财务损失,但延长的TR热响应时间为撤离提供可能。

表 4 部分BTM用阻燃PCM热物性及阻燃效果Table 4. Thermo-physical properties and flame retardant effects of flame retardant PCM for BTMPCM Flame

retardantMass fraction/

wt%Thermal

conductivity/

(W·m−1·K−1)Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Phase change

temperature/℃LOI/% Temperature

peak of TR/

℃Peak HRR before

and after

antiflaming/

(kW·m−2)Ref. OBC/EG/PW(13:5:70) AlCl3/Sb2O3/

glass fibrePadded 1.48 130.7/— 47.1/— 26.0 — 462.3/190.3 [59] Silica aerogel/PW(60:40) APP/dipentaerythritol Coated 0.05 79.2/— 39.6/— 56.3 691 — [60] Benzoyl peroxide/

EG/1,6-hexanediol diacrylate/octadecyl acrylate(4:12:6:318)Al(OH)3 15 1.26 71.5 46.1 — 639 242.5/204.4 [61] EG/SBS/PW(3:12:70) APP/phosphoric acid/ZnO 15 ~1 120.0 45.3 35.9 — 2980.0/801.0 [63] EG/ER/PW(4:50:80) APP/RP 38 1.10 81.2 45.0-48.0 27.6 — 870.9/313.1 [64] PW Aluminium trihydrate/

Mg(OH)250 — 115.0 50.0 — 364 29.0/15.5(kW) [65] PW APP 50 — 98.1 51.4 — 764 29.0/23.9(kW) [65] Polyester fiber/PEG APP 15 0.38 70.1 — 28.7 — 654.7/385.7 [66] Notes: PEG—Polyethylene glycol; APP—Ammonium polyphosphate; RP—Red phosphorus; TR—Thermal runaway; HRR—Heat release rate. PCM可燃风险无法彻底解决,添加阻燃剂后本身仍可燃,只能使TR发生后处于相对可控状态。SEM结果指出原因所在(图5),以APP为例,燃烧产生了碳层隔绝空气,但图5(a)中碳层薄且出现裸露,图5(b)中则有部分孔洞出现,难以实现高效阻燃。同时阻燃剂的添加比例相对较大甚至可达50wt%,复合PCM的潜热值普遍偏低,约在70~130 kJ·kg−1附近,作为相变冷却策略蓄/放热能力欠佳,但提升阻燃效果是有机PCM冷却BTM系统的创新性改良,高潜热高导热且阻燃效果优异的复合PCM值得进一步探索。

2. 相变材料与传统散热的耦合优化

除去有机PCM各项物性不足,其单独在BTM的使用仍存在一定局限,特别对于高能量容量的大型方形电池,相比于圆柱形电池其内部产热大且难以散失,更易出现热量的累积。由于PCM在完全相变后散热能力严重下降,必须保证用量。但实际电动汽车电池容积有限,因此需要耦合其他散热方式以提高BTM安全性、可靠性,即使PCM完全相变也可以维持系统散热。由于阻燃、柔性PCM的系统应用不多,本文介绍以表2中PW、PEG为基体的高导热复合PCM通过耦合3种传统散热方式实现在BTM应用的进展,分别是热管、液体和空气。

2.1 耦合热管的电池热管理系统

使用耦合热管的独特优势在于热管形状可塑、导热强、易加工并具有较高安全性,不同形状的热管可通过不同方式与系统耦合,保障系统温度且无需额外维护成本。图6为耦合热管后两种不同PCM散热策略,图6(a)中PCM强化热管冷凝端散热,其中平板热管增大了热管与锂电池的接触表面以提高蒸发端吸热效率,与方形锂电池的组合较常见。图6(b)中PCM强化电池散热,圆柱形电池产热被PCM吸收,热管蒸发端则吸收PCM热量。耦合热管系统结构简单,可进一步结合空冷促进热管冷凝端散热。

Zhang等[67]设计了以PW结合泡沫金属为PCM辅助热管散热的BTM系统,PCM强化了热管的热量交换,在电池温度过高或PCM完全相变后外加风扇增强对流。在不同放电倍率下电池最大温差相比于纯PCM系统下降0.1~0.6℃,最大放电倍率下为3.6℃,达到热管理要求。曲捷[69]设计了具有3层三维结构的脉动热管并用于BTM,热管热端插入盛满PCM的铝盒并通过恒压热源加热,在80~120 W的高功率下PW无需完全相变即可达到热平衡,热端温度维持在60℃以下。Putra等[70]的实验结果表明,在60 W热负荷下,使用热管电池温度降低了26.62℃,同时将高结晶度44号石蜡(德国鲁尔公司,RT44 HC)和热管耦合,电池最高温度降低幅度达33.42℃,维持在56℃附近。Abbas等[71]设计了6×6的加热器阵列模拟电池模块,使用PW填充间隙,并在每排加热器间插入平板热管辅助散热,热管蒸发段在PW内部吸热,冷凝段则伸出电池盒并用水冷降温,在每个加热器2 W的加热速率下其表面最高温被控制在50℃之内。

热管与PW的耦合使用将产生叠加效应进一步强化散热,特别是热管工质未过热时[72],并在电池放热温升过程中随PCM逐渐液化,换热顺序出现由PCM主导向热管主导逐渐转变的过程[73]。表5为PW基复合PCM耦合热管后BTM温控优化差异,由于热管换热通过蒸发段吸热使工质相变完成热量向冷凝段转移,因此有效传热系数取决于热管与电池接触表面、冷端冷凝方式及热管排布[67, 71, 74-75],通常采用热管与电池直接接触并提升接触面积和冷凝段换热以有效增强耦合散热效果。针对电池结构不同热管类型多样,耦合系统相比于单独使用热管,最高温分别降低为6.3、9.3℃,相比于单独使用PCM,降低幅度分别为1.4、2.1、8.5℃,热管结构、布置方式导致的散热差异明显,是BTM系统需要考虑的重要因素。由于热管只能对电池接触单侧强化换热[76],电池最大温差改善并不佳,降低幅度均小于2℃。同时热管作为散热器件其稳定性受倾角、工质流态等影响[77],在车辆复杂行驶工况下换热效率波动。因此设计热管自身和耦合结构,使其均匀稳定地实现电池散热仍是未来研究的趋势。

表 5 PW耦合热管BTM系统控温优化对比Table 5. Optimization of temperature control of PW coupled with heat pipe BTM systemPCM Charge/discharge rate T1 max and ΔT1 max/℃ T2 max and ΔT2 max/℃ Ref. RT44 HC 60 W 52.8/—

(heatpipe)45.9/— [70] PW 2 W 48.3/—

(heatpipe)39.0/— [71] EG/PW 10 W 47.2/5.9

(PCM)45.1/4.7 [68] EG/PW 3 C 45.5/2.5(PCM) 44.1/1.7 [74] Copper foam/PW 5 C 52.5/4.2(PCM) 44.9/3.6 [67] Notes: T1 max and ΔT1 max—Maximum temperature and maximum temperature difference with single cooling method; T2 max and ΔT2 max—Maximum temperature and maximum temperature difference with coupled cooling method; RT44 HC—Rubitherm 44 high crystallinity. 2.2 耦合液冷或空冷的电池热管理系统

液冷、空冷的散热方式系统简单、研究相对成熟。但空冷散热受限于空气的低热导率和比热,液冷管路通常与电池组底部接触[52],不利于均匀散热。因此出现了液冷或空冷耦合PCM的高效、低能耗复合冷却方式。二者的共同之处在于,选择合适的液体、空气流道能有效增强换热和改善散热不均。图7为耦合不同液冷或空冷系统结构示意图,基于不同管路排布对散热效果进行了实验评估,图7(a)的蜂窝式液体管路以六边形结构环绕电池组,图7(b)的错排往复流道从电池一侧流经下底面至另一侧往复循环,增大与电池接触范围以实现均匀散热。图7(c)中空气经过扁平空腔流经PCM模块,换热面积增大、换热效率提升,图7(d)中的电池以4×8错排,接触面布置蛇形PCM,上方用风冷辅助散热,蛇形通道增大PCM与空气接触面积的同时加剧空气扰动,有效提升了对流换热系数。

Yang等[78]提出的蜂窝状BTM系统在六边形冷却板上分布液体微通道并均匀嵌入电池,上下用铝合金冷却板密封,在32.2 A电流下电池模块最高温度和温差稳定在39℃和3.5℃。Hekmat等[79]考虑到铝管不同布置方式,实验结果表明在多管路水冷和PEG 1000耦合散热下系统最高温度和最大温差为30/0.6℃,远小于自然冷却的58/7.4℃,温控效果也优于单独使用PCM被动式热管理的32/1.2℃。Akbarzadeh 等[82]设计了新型液冷板以EG/PW冷却液体流道,并安装在电池模块的侧壁,与普通铝制冷却板相比效果优异,在0.5、0.75、1 L/min流速下可分别降低21%、24%、30%的能耗。Mashayekhi 等[83]同样在电池模块侧壁均匀液冷散热,并用泡沫铜/PW复合PCM填充间隙。在12.5 W生热功率下,在液冷系统最高温达到60℃时,耦合液冷系统电池表面温度仅为45.1℃。Lv等[81]设计的蛇形PCM外加强迫空气对流的散热管理方案,在2 C充电倍率、风扇功率5.2 W循环放电过程中,蛇形PCM电池最高温度仅为51.9℃,相比于块状PCM低3.6℃,证明空气流道对换热的增强显著。Safdari 等[25]分别以PEG 1000和PEG 1500为PCM,对混合空气制冷的BTM系统进行优化,探究了空气间隙和空气流速对系统制冷效果的改善。结果发现,空气流速的增大可以有效降低电池最高温,但对电池温差的改善则需要通过增大空气间隙实现,在2 C充电和1 C放电倍率下,该系统可维持电池表面平均温度低于37℃。Lazrak 等[84]用透明树脂玻璃封装电池,内部缠绕铜丝增强导热,填充PW后用铝板上下密封。并外加风扇对上下铝板水平吹风进行对流散热,实验得出结论电池发热量为2.45 W时最高温度/最大温差被控制在30/5℃内。

表6为耦合液冷或空冷后BTM系统前后温度差异的实验结果,在已有液冷或空冷散热下耦合PCM,系统最高温度下降幅度在8.9~10.8℃,下降幅度较大且不同PCM的差异并不明显。而相比于单独使用PCM,耦合液冷系统最高温达到25~45.1℃,下降约2~14℃;耦合风冷系统最高温为25.6~51.9℃,下降幅度在4.9~17℃间,波动范围较大,说明液体管路、流速或空气流道对散热具有显著性影响。即使5 C的高放电倍率下耦合系统均满足最高温低于50℃,不同工况最大温差最高值仅为4℃,能耗也有所降低,满足热管理需求。学者们对蜂窝式、内嵌式、侧板式等创新流体通道进行实验,优化电池表面气流组织,尝试了改变管内工质和管径增强系统均在高放电倍率下具有均匀散热特性,对现有车用液冷/空冷结构革新提出宝贵建议。

表 6 耦合液冷或空冷后BTM系统控温优化Table 6. Optimization of temperature control of BTM system coupled with liquid cooling or air coolingPCM Method of coupling Charge/discharge rate T1 max and ΔT1 max/℃ T2 max and ΔT2 max/℃ Ref. h-BN/SEBS/PW Liquid cooling 5 C 52.9/7.9

(Liquid cooling)44.0/3.2 [52] PEG 1000 Liquid cooling 0.9 C 32.0/1.2(PEG 1000) 30.0/0.6 [79] Copper foam/PW Liquid cooling 12.5 W 60.0/—

(Liquid cooling)45.1/— [83] EG/RT44 HC Liquid cooling 2 C 50.0/4.1

(Liquid cooling)42.0/1.2 [85] EG/Lipin/PW Liquid cooling 3 C 45.10/—

(PCM)41.1/4.0 [86] Copper foam/RT25 HC Liquid cooling 2 C 39.00/—

(RT25 HC)25.0/1.0 [87] Aluminium foam/RT27 Air cooling 1 C — 25.6/— [82] Copper foam/PW Air cooling 5 W 46.6/—

(Air cooling)35.8/— [80] Cetane stearic acid/EG/PW Air cooling 2 C — 51.9/2.6 [81] PEG 1000 Air cooling 2 C — 37.0/— [25] Copper wire/PW Air cooling 2.45 W 43.0/—

(PCM)26.0/— [84] 3. 复合热管理系统的模拟仿真

随着计算流体力学、数值传热学等利用计算机实现离散化的数值模拟方法逐渐成熟,学者们选择借助Ansys Fluent、Comsol Multiphysics等仿真软件对复杂系统和工况下PCM的热管理效果进行评估。基于电化学与能量平衡方程下的数学模型[88-89]计算电池产热速率,并利用等效比热容模型[90]或焓模型[91]构建PCM蓄放热过程能量控制方程和相关离散化方程以表达热传导过程,通过网格无关和实验比对验证模型可靠性后,用于减少实验重复或分析复杂散热工况下电池温度场分布。表7为几种常用数学模型的定义式,电池产热简化为等效内阻产热和熵变产热之和,PCM吸热则通过焓值或比热随温度的变化实现。

表 7 BTM仿真模拟常用的3种数学物理模型Table 7. 3 kinds of mathematical and physical models commonly used in BTM simulationModel Equation of definition Parameter Ref. Electrochemical heat

generation modelq=RiI2−IT∂U∂T Notes: Ri—Equivalent internal resistance of the battery; I—Current; T—Temperature of battery; q—Heat flux; U—Voltage. [92] Effective heat capacity model ρcp(T)∂T∂t=λ∂2T∂x2

cp={cps,T<Tc−ΔTL2ΔT+cps+cpl2,Tc−ΔT⩽Notes: L—Liquid fraction; λ—Thermal conductivity; t—Time; x—Distance; cps, cpl—Specific heat capacities of solid and liquid PCM respectively; ΔT—Half of phase change temperature range; Tc—Cent temperature of the phase change temperature range. [93] Enthalpy model \begin{gathered} \rho \dfrac{{\partial H}}{{\partial t}} = \lambda \dfrac{{{\partial ^2}T}}{{\partial {x^2}}} \\ H = \int_{{T_0}}^T {{c_{\rm p}}dT} + \beta \gamma \\ \left\{ \begin{gathered} \beta = 0,T < {T_{\rm s}}{\text{ }} \\ \beta = 0,T > {T_{\rm l}} \\ \beta = \dfrac{{T - {T_{\rm s}}}}{{{T_{\rm l}} - {T_{\rm s}}}},{T_{\rm s}} < T < {T_{\rm l}} \\ \end{gathered} \right. \\ \end{gathered} Notes: ρ—Density; H—Total enthalpy; T0—Temperature when the enthalpy is 0 kJ·kg−1; β—Liquid fraction; γ—Latent heat; Ts and Tl—Solidification and melting temperatures of PCM, respectively. [94] Jin等[95]以一维电化学模型和三维热模型建立了正十八烷与热管耦合的BTM系统,利用电池固体传热界面的动态热性能参数和传输参数求解温度场,忽略电化学反应产生的气体以及高温下电池副反应。仿真结果显示,热管有效改善了单一PCM板电池散热性能,在3 C倍率下最高温度和最大温差由28.5/3.09℃降低至28.39/2.99℃。Chen等[94]考虑到复合PCM的定型效果,忽略其相变时的自然流动和体积膨胀,以焓模型法模拟PCM的融化凝固过程,同时采用基于电池充电状态(State of charge,SOC)的多项放热模型[96]和常数放热模型。比较了耦合PW和热管的BTM系统与只用热管进行热管理的差异,两种产热模型下电池温度偏差为0.16℃,且与实验结果吻合,偏差仅0.61℃。仿真结果显示,耦合系统内部最高温度及最大温差均得到有效控制,较后者分别下降9.8℃和3.3℃,进一步调整PCM厚度分布后发现, PCM含量的提升降低了系统最高温度,但PCM的熔化差异却导致了更高的电池温差。Wang等[97]以焓模型法和电-热模型仿真模拟底部、单面和双面液冷板对PCM散热的强化效果,靠近液冷板侧温度下降明显,但相比于纯PCM,远离液冷板处温度反而上升,导致局部温差增大,双面液冷效果最佳,降低电池表面最高温度至46.3℃。Yi等[98]除使用焓模型法和多项放热模型给出PCM和电池的传热控制方程外,还将电池产热分为电池和电极两部分,发现在大空间自然对流下电池以1 C倍率放电的模拟结果与实验基本吻合。随后设计了PW与液冷耦合模型研究了冷却剂流量、管径等参数对冷却性能的影响。结果如图8所示,随流量增大,对流换热系数和努塞尔数(Nu)数随之增大但温度与流量的斜率减小,意味着换热效果的提升有限;随管径增大PW的平均对流换热系数减小,Nu数增大,传热速率明显提高。

Yang等[93]基于电化学反应的三维流动换热模型,以等效比热容法处理PCM传热,比较了电池组在自然对流、自然对流耦合PW及强制对流耦合PW 3种工况循环放电时的热性能。1 C放电倍率下,相比于自然对流,后两种方式使系统最高温度进一步下降18.3℃和23.4℃。Leng等[73]在考虑自然对流情况下,以集总参数法简化热管传热,通过等效比热容模型实现PCM相变蓄热,耦合后的热管理系统温度分布如图9(a)所示。与单独使用PCM相比,PCM融化所用时间延长约一倍,随后系统温度上升,直至与单独使用热管的系统温度持平。

以上仿真案例通过建立温度与焓或比热容的关系,能够准确反映PCM在熔化/凝固过程中的蓄/放热变化,对于电池内部的复杂反应,通过合理假设节省计算资源,同时反映表面温度场变化。与实验结果极小误差体现了仿真模拟的真实准确,从而对复杂工况下的电池热管理进行有效评价,优化了冷却条件。如图9所示,耦合热管、液冷、空冷的不同BTM系统散热效果均可通过仿真评价,减少实验重复和测量误差,与单独散热方式相比,仿真显示耦合系统的优化明显。不同于实验的是,无外加条件影响其结果表现出一定相似,图9(b)、图9(c)中的循环过程前后波峰变化并不明显。同时仿真模拟的创新性相对不足,已有的PCM、电池模型往往源自以往的经验归纳或半经验理论,从理论出发对现有实验特性变化进行合理有据的描述或对实验趋势进行预测,仍需要进一步研究。

4. 结语与展望

4.1 结语

锂离子电池工作状态下的温度控制问题是限制新能源产业发展的一大难点。本文总结了近些年从热导率的提高、力学性能改善及材料的强化阻燃效果方面对复合有机相变材料(PCM)的物性改进,同时概括了不同散热方式的耦合冷却及其仿真对比,结论如下:

(1) 在材料的改性方面,目前PCM热导率提升主要通过与其他材料进行物理、化学共混实现。膨胀石墨(EG)对热导率的提升效果要远高于其他碳材料或纳米颗粒,其有效吸附性同时对过冷度提升显著,在电池热管理(BTM)中实用性更高,泡沫金属对热导率的提升也十分可观,但二者均为电的良导体,作为BTM材料存在安全隐患。提高柔性和阻燃性的研究仍较少,主要是向有机PCM中混入共聚物弹性体或商业化阻燃剂,柔性PCM可达到普遍小于1 MPa的抗拉强度;阻燃PCM的极限氧指数(LOI)达26%~56.3%,峰值热释放率(HRR)在190~801 kW·m−2不等。其弊端在于柔性PCM的高温热致柔性影响电池寿命,阻燃剂的添加也未能完全阻止燃烧,并都在一定程度降低复合材料潜热;

(2) PCM与传统散热方式的耦合显著强化电池组散热,耦合热管BTM系统构造简单,相比于单独使用PCM,系统最高温降低幅度达1.4~8.5℃,但对温差改善小于2℃;复合液冷或空气方式通过改变流量和风速适应不同放电倍率下的散热,需要合理的管道排布或气流组织以保证BTM热均匀性,系统最高温分别下降2~14℃和17℃,最大温差均在4℃内,商业化前景优异,其缺点是增加管路和风扇使系统相对冗杂;

(3) 通过不同数学物理模型,耦合热管、液冷、空冷的不同BTM系统散热效果均可通过仿真评估,仿真模拟已经能实现与实验的微小误差,优化复杂工况下工作条件,但现有仿真模拟的创新性相对不足,对电池内部化学反应、热管内部多相流体等复杂情况导致的热传递往往采取简化处理。

4.2 展望

本文综述了近年来BTM的进展,但使用有机PCM进行BTM仍有不足需要改善。

(1) 首先烷烃类PCM价格昂贵,难以作为实际应用材料。有机固-液PCM的研究仍集中于石蜡,加入EG和泡沫金属提高热导率的同时增强了材料的导电性能,增加电池短路损毁的潜在可能;柔性PCM的柔性温度普遍高于电池正常工作温度,易缩短电池使用寿命;复合有机阻燃PCM自身仍存在可燃风险,热导率和潜热等物性也随阻燃剂的添加相应降低。因此,合理平衡材料的导热性、柔韧性、导电性等物性关系仍是关乎实际应用的研究重点,同时考虑相变点不同的PCM延长对电池升温过程的多级散热,或许是改善BTM的另一方向。

(2) 耦合不同的散热方式提高了BTM控温效果,但对系统本身构造和稳定性提出考验。系统构造需要高成本投入和一定的安全风险,考虑PCM封装后与电池的贴合或能提高稳定性、降低维护成本。仿真模拟已实现低误差下BTM系统的温度场求解,通过进一步改进现有数学物理模型,利用仿真模拟进行工况优化,合理考虑管路排布、PCM用量,在满足热管理需求的前提减少电池箱配重和冗余组件,保证系统稳定低维护,这是未来将PCM与BTM真正结合的必经之路。

-

表 1 部分用于电池热管理(BTM)的有机固-液相变材料(PCM)热物性

Table 1 Thermo-physical properties of organic solid-liquid phase change materials (PCM) for battery thermal management (BTM)

PCM Thermal conductivity/(W·m−1·K−1) Latent heat/(kJ·kg−1) Phase change temperature/

℃Ref. Paraffin(PW) 0.2 255 41-44/— [20] PW 0.22 300 36/— [21] PW 0.21 200 40/— [22] Lauric acid 0.15 177 43/— [23] Myristic acid — 187 53.7/— [23] Palmitic acid 0.17 186 62.3/— [23] Stearic acid 0.17 203 70.7/— [23] Capric acid 0.15 152.7 28.9/31.9 [24] Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 600 — 146 20-25 [23] PEG 1000 0.29 142/— 35.9/29.9 [25] PEG 1500 0.31 163.4/— 48.9/42.9 [25] PEG 3400 — 171.6 56.4 [23] Tetradecanol — 205 38 [26] 1-dodecanol — 200 26 [26] 表 2 BTM用有机PCM热导率强化及其热物性

Table 2 Thermal conductivity enhancements and thermo-physical properties of organic PCM for BTM

PCM and

additivesMass fraction Thermal conductivity

of pure PCM/

(W·m−1·K−1)Thermal conductivity of

composite PCM/

(W·m−1·K−1)Phase change

temperature/

℃Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Ref. EG/PW 20∶80 0.15 1.90 — — [29] GNP/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.87 — — [29] CNT/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.37 — — [29] Graphene/PW 20∶80 0.15 0.49 — — [29] Nano-Al/PW 20∶80 0.25 0.78 53.89/49.46 282.50/281.20 [30] Nano-TiO2/PW 20∶80 0.25 0.43 54.28/50.74 283.09/280.64 [30] AlN/EG/ER/PW 20∶3∶27∶50 0.20 4.33 47.20/— 116.30 [33] EG/ER/copper foam/PW — 0.23 2.90 49.80/— 75.00 [36] sw-GS/PW 2.25∶97.75 0.19 2.58 53.50/45.40 172.50/158.90 [37] NPC-Al/PEG 2000 15∶85 0.27 0.41 54.40/— 155.30/— [38] CNT/MOFs/PEG 2000 5.16∶24.84∶70 0.30 0.46 52.40/27.40 96.20/90.10 [39] MWCNT/graphene/PW 0.3∶0.7∶99 0.39 0.87 45.30/40.80 203.80/198.00 [40] EG/PW 10∶90 0.28 6.4 39.50 187.88 [42] CNT/PW 10∶90 0.28 0.39 40.30 172.62 [42] h-BN/Na2SiO3/PW 18∶0.9∶81.1 0.12 0.85 52.30/47.90 165.40/176.10 [43] EG/aluminum foam/graphene/PW — 0.20 7.1 — — [44] NPC/myristic acid-stearic acid 12∶26.4∶61.6 0.17 0.37 49.45/— 164.33/— [45] EG/SiO2/low-density polyethylene/RT 45 7∶5.5∶30∶57.5 — 3.30 44.00 77.80 [46] Notes: EG—Expanded graphite; GNP—Graphene nanosheets; CNT—Carbon nanotubes; ER—Epoxy resin; MWCNT—Multi-walled carbon nanotubes; NPC—N-doped porous carbons; RT 45—Rubitherm 45. 表 3 BTM用有机PCM柔性强化及其热物性

Table 3 Flexibility enhancements and thermo-physical properties of organic PCM for BTM

PCM and

additivesThermal

conductivity/

(W·m−1·K−1)Phase change

temperature/

℃Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Mechanical property Ref. Test temperature/℃ Tensile and

bending

strength/MPaModulus of

elasticity/

MPaEG/SBS/TPEE/PW(5:10:5:80) 1.20(30℃) 56.7/— 172.6/— 60 0.09/— — [47] EG/TPC-et/PW(10:45:45) 1.64 46.4/— 102.0 25 0.88/0.14 — [48] EG/OBC/PW(10:45:45) 1.57 50.1/— 101.0 25 5.44/1.21 — [48] EVA/EG/PW(47.5:5:47.5) 1.70 53.0 121.0 30 0.83/0.02 — [49] SEPS/EG/PW(9.5:5:85.5) 2.67 48.0/— 211.9 50 — — [50] SBS/AlN/PW(50:15:35) 0.50 46.8 57.1 50 0.16/0.16 67.00 [51] h-BN/SEBS/PW(20:20:60) 2.80 40.1-44.3/— 148.3 — — 0.72 [52] EG/SBS/EPDM/PW(5:12:3:80) 1.25 50.9/— 133 60 0.51/— — [53] OBC/EG/PW(19:5:76) 2.34 39.5 185.4 60 — 63.90 [54] SBS/EG/PW(60:3:57) 0.88 50.6 78.3 — 0.34/0.51 — [55] EG/SEBS/PW(5:20:80) 1.23 47.4 159.2/166.5 — — — [56] OBC/EG/eicosane(20:3:80) 1.21 33.5 170.2 — — — [57] OBC/EG/tetracosane(20:3:80) 1.18 47.4 175.1 — — — [57] HDPE/EG/eicosane(20:3:80) 1.25 33.4 169.0 — — — [57] EG/silicon rubber/h-BN/PW(3:55:5:28) 0.95 47.3/— 62.7 — 0.53/— — [58] Notes: TPC-et—Copolyester thermoplastic elastomer with polyether soft segment; OBC—Olefin block copolymer; EVA—Ethylene vinylacetate; SEPS—Styrene butene propylene styrene; SEBS—Styrene ethylene butylene styrene; HDPE—High density polyethylene. 表 4 部分BTM用阻燃PCM热物性及阻燃效果

Table 4 Thermo-physical properties and flame retardant effects of flame retardant PCM for BTM

PCM Flame

retardantMass fraction/

wt%Thermal

conductivity/

(W·m−1·K−1)Latent

heat/

(kJ·kg−1)Phase change

temperature/℃LOI/% Temperature

peak of TR/

℃Peak HRR before

and after

antiflaming/

(kW·m−2)Ref. OBC/EG/PW(13:5:70) AlCl3/Sb2O3/

glass fibrePadded 1.48 130.7/— 47.1/— 26.0 — 462.3/190.3 [59] Silica aerogel/PW(60:40) APP/dipentaerythritol Coated 0.05 79.2/— 39.6/— 56.3 691 — [60] Benzoyl peroxide/

EG/1,6-hexanediol diacrylate/octadecyl acrylate(4:12:6:318)Al(OH)3 15 1.26 71.5 46.1 — 639 242.5/204.4 [61] EG/SBS/PW(3:12:70) APP/phosphoric acid/ZnO 15 ~1 120.0 45.3 35.9 — 2980.0/801.0 [63] EG/ER/PW(4:50:80) APP/RP 38 1.10 81.2 45.0-48.0 27.6 — 870.9/313.1 [64] PW Aluminium trihydrate/

Mg(OH)250 — 115.0 50.0 — 364 29.0/15.5(kW) [65] PW APP 50 — 98.1 51.4 — 764 29.0/23.9(kW) [65] Polyester fiber/PEG APP 15 0.38 70.1 — 28.7 — 654.7/385.7 [66] Notes: PEG—Polyethylene glycol; APP—Ammonium polyphosphate; RP—Red phosphorus; TR—Thermal runaway; HRR—Heat release rate. 表 5 PW耦合热管BTM系统控温优化对比

Table 5 Optimization of temperature control of PW coupled with heat pipe BTM system

PCM Charge/discharge rate T1 max and ΔT1 max/℃ T2 max and ΔT2 max/℃ Ref. RT44 HC 60 W 52.8/—

(heatpipe)45.9/— [70] PW 2 W 48.3/—

(heatpipe)39.0/— [71] EG/PW 10 W 47.2/5.9

(PCM)45.1/4.7 [68] EG/PW 3 C 45.5/2.5(PCM) 44.1/1.7 [74] Copper foam/PW 5 C 52.5/4.2(PCM) 44.9/3.6 [67] Notes: T1 max and ΔT1 max—Maximum temperature and maximum temperature difference with single cooling method; T2 max and ΔT2 max—Maximum temperature and maximum temperature difference with coupled cooling method; RT44 HC—Rubitherm 44 high crystallinity. 表 6 耦合液冷或空冷后BTM系统控温优化

Table 6 Optimization of temperature control of BTM system coupled with liquid cooling or air cooling

PCM Method of coupling Charge/discharge rate T1 max and ΔT1 max/℃ T2 max and ΔT2 max/℃ Ref. h-BN/SEBS/PW Liquid cooling 5 C 52.9/7.9

(Liquid cooling)44.0/3.2 [52] PEG 1000 Liquid cooling 0.9 C 32.0/1.2(PEG 1000) 30.0/0.6 [79] Copper foam/PW Liquid cooling 12.5 W 60.0/—

(Liquid cooling)45.1/— [83] EG/RT44 HC Liquid cooling 2 C 50.0/4.1

(Liquid cooling)42.0/1.2 [85] EG/Lipin/PW Liquid cooling 3 C 45.10/—

(PCM)41.1/4.0 [86] Copper foam/RT25 HC Liquid cooling 2 C 39.00/—

(RT25 HC)25.0/1.0 [87] Aluminium foam/RT27 Air cooling 1 C — 25.6/— [82] Copper foam/PW Air cooling 5 W 46.6/—

(Air cooling)35.8/— [80] Cetane stearic acid/EG/PW Air cooling 2 C — 51.9/2.6 [81] PEG 1000 Air cooling 2 C — 37.0/— [25] Copper wire/PW Air cooling 2.45 W 43.0/—

(PCM)26.0/— [84] 表 7 BTM仿真模拟常用的3种数学物理模型

Table 7 3 kinds of mathematical and physical models commonly used in BTM simulation

Model Equation of definition Parameter Ref. Electrochemical heat

generation modelq = {R_{\rm{i}}}{I^2} - IT\dfrac{{\partial U}}{{\partial T}} Notes: Ri—Equivalent internal resistance of the battery; I—Current; T—Temperature of battery; q—Heat flux; U—Voltage. [92] Effective heat capacity model \rho {c_{\rm{p}}}(T)\dfrac{{\partial T}}{{\partial t}} = \lambda \dfrac{{{\partial ^2}T}}{{\partial {x^2}}}

{c_{\rm p}} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} {c_{\rm ps}},T < {T_{\rm c}} - \Delta T \\ \dfrac{L}{{2\Delta T}} + \dfrac{{{c_{\rm ps}} + {c_{\rm pl}}}}{2},{T_{\rm c}} - \Delta T \leqslant T \leqslant {T_{\rm c}} + \Delta T \\ {c_{\rm pl}},T > {T_{\rm c}} + \Delta T \\ \end{gathered} \right.Notes: L—Liquid fraction; λ—Thermal conductivity; t—Time; x—Distance; cps, cpl—Specific heat capacities of solid and liquid PCM respectively; ΔT—Half of phase change temperature range; Tc—Cent temperature of the phase change temperature range. [93] Enthalpy model \begin{gathered} \rho \dfrac{{\partial H}}{{\partial t}} = \lambda \dfrac{{{\partial ^2}T}}{{\partial {x^2}}} \\ H = \int_{{T_0}}^T {{c_{\rm p}}dT} + \beta \gamma \\ \left\{ \begin{gathered} \beta = 0,T < {T_{\rm s}}{\text{ }} \\ \beta = 0,T > {T_{\rm l}} \\ \beta = \dfrac{{T - {T_{\rm s}}}}{{{T_{\rm l}} - {T_{\rm s}}}},{T_{\rm s}} < T < {T_{\rm l}} \\ \end{gathered} \right. \\ \end{gathered} Notes: ρ—Density; H—Total enthalpy; T0—Temperature when the enthalpy is 0 kJ·kg−1; β—Liquid fraction; γ—Latent heat; Ts and Tl—Solidification and melting temperatures of PCM, respectively. [94] -

[1] 邓林旺, 冯天宇, 舒时伟, 等. 锂离子电池快充策略技术研究进展[J]. 储能科学与技术, 2022, 11(9):2879-2890. DOI: 10.19799/j.cnki.2095-4239.2021.0635 DENG Linwang, FENG Tianyu, SHU Shiwei, et al. A review of fast charging strategy and technology for lithium-ion batteries[J]. Energy Storage Science and Technology,2022,11(9):2879-2890(in Chinese). DOI: 10.19799/j.cnki.2095-4239.2021.0635

[2] LEI S R, SHI Y, CHEN G Y. A lithium-ion battery-thermal-management design based on phase-change-material thermal storage and spray cooling[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,168:114792. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114792

[3] 刘霏霏, 鲍荣清, 程贤福, 等. 服役工况下车用锂离子动力电池散热方法综述[J]. 储能科学与技术, 2021, 10(6):2269-2282. LIU Feifei, BAO Rongqing, CHENG Xianfu, et al. Review on heat dissipation methods of lithium-ion power battery for vehicles under service conditions[J]. Energy Storage Science and Technology,2021,10(6):2269-2282(in Chinese).

[4] PANCHAL S, DINCER I, AGELIN-CHAAB M, et al. Transient electrochemical heat transfer modeling and experimental validation of a large sized LiFePO4/graphite battery[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2017,109:1239-1251. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.03.005

[5] PANCHAL S, RASHID M, LONG F, et al. Degradation testing and modeling of 200 Ah LiFePO4 battery[Z]. SAE International. 2018.

[6] XU X M, HE R. Research on the heat dissipation performance of battery pack based on forced air cooling[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2013,240:33-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.03.004

[7] CHEN F F, HUANG R, WANG C M, et al. Air and PCM cooling for battery thermal management considering battery cycle life[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,173:115154. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115154

[8] YUKSEL T, LITSTER S, VISWANATHAN V, et al. Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle LiFePO4 battery life implications of thermal management, driving conditions, and regional climate[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2017,338:49-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.10.104

[9] LAN C J, XU J, QIAO Y, et al. Thermal management for high power lithium-ion battery by minichannel aluminum tubes[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2016,101:284-292. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.02.070

[10] SHANG Z Z, QI H Z, LIU X T, et al. Structural optimization of lithium-ion battery for improving thermal performance based on a liquid cooling system[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2019,130:33-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.10.074

[11] LIU J W, LI H, LI W Y, et al. Thermal characteristics of power battery pack with liquid-based thermal management[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,164:114421. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114421

[12] LIU F F, LAN F C, CHEN J Q. Dynamic thermal characteristics of heat pipe via segmented thermal resistance model for electric vehicle battery cooling[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2016,321:57-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.04.108

[13] RAO Z H, WANG S F, WU M C, et al. Experimental investigation on thermal management of electric vehicle battery with heat pipe[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2013,65:92-97. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2012.08.014

[14] 陈萌, 李静静. 脉动热管用于电动汽车锂电池散热性能试验[J]. 化工进展, 2021, 40(6):3163-3171. DOI: 10.16085/j.issn.1000-6613.2020-1400 CHEN Meng, LI Jingjing. Experiment on heat dissipation performance of electric vehicle lithium battery based on pulsating heat pipe[J]. Chemical Progress,2021,40(6):3163-3171(in Chinese). DOI: 10.16085/j.issn.1000-6613.2020-1400

[15] ZHANG N, YUAN Y P, CAO X L, et al. Latent heat thermal energy storage systems with solid-liquid phase change materials: A review[J]. Advanced Engineering Materials,2018,20(6):1700753. DOI: 10.1002/adem.201700753

[16] AHMADI Y, KIM K H, KIM S, et al. Recent advances in polyurethanes as efficient media for thermal energy storage[J]. Energy Storage Materials,2020,30:74-86. DOI: 10.1016/j.ensm.2020.05.003

[17] NAZIR H, BATOOL M, BOLIVAR OSORIO F J, et al. Recent developments in phase change materials for energy storage applications: A review[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2019,129:491-523. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.09.126

[18] ZHANG P, XIAO X, MA Z W. A review of the composite phase change materials: Fabrication, characterization, mathematical modeling and application to performance enhancement[J]. Applied Energy,2016,165:472-510. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.12.043

[19] LILLEY D, LAU J, DAMES C, et al. Impact of size and thermal gradient on supercooling of phase change materials for thermal energy storage[J]. Applied Energy,2021,290:116635. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116635

[20] ZHANG F R, ZHAI L, ZHANG L, et al. A novel hybrid battery thermal management system with fins added on and between liquid cooling channels in composite phase change materials[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2022,207:118198. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.118198

[21] LAMRANI B, LEBROUHI B E, KHATTARI Y, et al. A simplified thermal model for a lithium-ion battery pack with phase change material thermal management system[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2021,44:103377. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2021.103377

[22] ZHOU Z Z, WANG D, PENG Y, et al. Experimental study on the thermal management performance of phase change material module for the large format prismatic lithium-ion battery[J]. Energy,2022,238:122081. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122081

[23] 金露, 谢鹏, 赵彦琦, 等. 基于相变材料的电动汽车电池热管理研究进展[J]. 材料导报, 2021, 35(21):21113-21126. JIN Lu, XIE Peng, ZHAO Yanqi, et al. Research progress on phase change material based thermal management system of EV batteries[J]. Materials Reports,2021,35(21):21113-21126(in Chinese).

[24] VERMA A, SHASHIDHARA S, RAKSHIT D. A comparative study on battery thermal management using phase change material (PCM)[J]. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress,2019,11:74-83. DOI: 10.1016/j.tsep.2019.03.003

[25] SAFDARI M, AHMADI R, SADEGHZADEH S. Numerical and experimental investigation on electric vehicles battery thermal management under new european driving cycle[J]. Applied Energy,2022,315:119026. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119026

[26] 王忠良, 王子晨, 陈昌建, 等. 相变材料在动力电池中的应用研究进展[J]. 硅酸盐学报, 2021, 49(6):1065-1077. WANG Zhongliang, WANG Zichen, CHENG Changjian, et al. Development on application of phase change materials in electric vehicle power batteries[J]. Journal of the Chinese Ceramic Society,2021,49(6):1065-1077(in Chinese).

[27] 孙文鸽, 韩磊, 吴志根. 膨胀石墨/石蜡相变复合材料有效导热系数的数值计算[J]. 复合材料学报, 2015, 32(6):1596-1601. SUN Wen'ge, HAN Lei, WU Zhigen. Numerical calculation of effective thermal conductivity coefficients of expanded graphite/paraffin phase change composites[J]. Acta Materiae Compositae Sinica,2015,32(6):1596-1601(in Chinese).

[28] 刘臣臻, 张国庆, 王子缘, 等. 膨胀石墨/石蜡复合材料的制备及其在动力电池热管理系统中的散热特性[J]. 新能源进展, 2014, 2(3):233-238. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-560X.2014.03.011 LIU Chenzhen, ZHANG Guoqing, WANG Ziyuan, et al. Preparation of expanded graphite/paraffin composite materials and their heat dissipation characteristics in power battery thermal management system[J]. Progress of New Energy,2014,2(3):233-238(in Chinese). DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-560X.2014.03.011

[29] NOH Y J, KIM H S, KU B C, et al. Thermal conductivity of polymer composites with geometric characteristics of carbon allotropes [J]. Advanced Engineering Materials,2016,18(7):1127-1132. DOI: 10.1002/adem.201500451

[30] WARZOHA R J, FLEISCHER A S. Improved heat recovery from paraffin-based phase change materials due to the presence of percolating graphene networks[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2014,79:314-323. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.08.009

[31] KUMAR R, MITRA A, SRINIVAS T. Role of nano-additives in the thermal management of lithium-ion batteries: A review[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2022,48:104059. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2022.104059

[32] LI J M, TANG A K, SHAO X, et al. Experimental evaluation of heat conduction enhancement and lithium-ion battery cooling performance based on h-BN-based composite phase change materials[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2022,186:122487. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122487

[33] ZHANG J Y, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Characterization and experimental investigation of aluminum nitride-based composite phase change materials for battery thermal management[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2020,204:112319. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112319

[34] ZHOU T L, WANG X, LIU X H, et al. Improved thermal conductivity of epoxy composites using a hybrid multi-walled carbon nanotube/micro-SiC filler[J]. Carbon,2010,48(4):1171-1176. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbon.2009.11.040

[35] MOEINI S M, KHODADADI J M. Thermal conductivity improvement of phase change materials/graphite foam composites[J]. Carbon,2013,60:117-128. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.04.004

[36] HE J S, YANG X Q, ZHANG G Q. A phase change material with enhanced thermal conductivity and secondary heat dissipation capability by introducing a binary thermal conductive skeleton for battery thermal management[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2019,148:984-991. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.11.100

[37] LIN Y, KANG Q, WEI H, et al. Spider web-inspired graphene skeleton-based high thermal conductivity phase change nanocomposites for battery thermal management[J]. Nano-Micro Letters,2021,13(11):316-329.

[38] ATINAFU D G, DONG W, HOU C, et al. A facile one-step synthesis of porous N-doped carbon from MOF for efficient thermal energy storage capacity of shape-stabilized phase change materials[J]. Materials Today Energy,2019,12:239-249. DOI: 10.1016/j.mtener.2019.01.011

[39] WANG J J, HUANG X B, GAO H Y, et al. Construction of CNT@Cr-MIL-101-NH2 hybrid composite for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal conductivity[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal,2018,350:164-172. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.05.190

[40] ZOU D Q, MA X F, LIU X S, et al. Thermal performance enhancement of composite phase change materials (PCM) using graphene and carbon nanotubes as additives for the potential application in lithium-ion power battery[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2018,120:33-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.12.024

[41] WU S F, YAN T, KUAI Z H, et al. Thermal conductivity enhancement on phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A review[J]. Energy Storage Materials,2020,25:251-295. DOI: 10.1016/j.ensm.2019.10.010

[42] 王文健. 基于复合相变材料的锂离子电池热管理系统传热强化研究[D]. 徐州: 中国矿业大学, 2018. WANG Wenjian. Investigation on the heat transfer enhancement of lithium ion battery thermal management system based on composite phase change material[D]. Xuzhou: China University of Mining and Technology, 2018(in Chinese).

[43] QIAN Z C, SHEN H, FANG X, et al. Phase change materials of paraffin in h-BN porous scaffolds with enhanced thermal conductivity and form stability[J]. Energy and Buildings,2018,158:1184-1188. DOI: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.11.033

[44] 黄菊花, 陈强, 曹铭, 等. 石蜡/膨胀石墨/石墨烯/铝蜂窝复合相变材料的制备及锂电池控温性能研究[J]. 化工新型材料, 2022, 50(2):140-144, 149. DOI: 10.19817/j.cnki.issn1006-3536.2022.02.028 HUANG Juhua, CHEN Qiang, CAO Ming, et al. Research on preparation of PW/EG graphite/graphene/Al honeycomb and temperature control performance of lithium battery[J]. New Chemical Materials,2022,50(2):140-144, 149(in Chinese). DOI: 10.19817/j.cnki.issn1006-3536.2022.02.028

[45] ATINAFU D G, DONG W, HUANG X, et al. Introduction of organic-organic eutectic PCM in mesoporous N-doped carbons for enhanced thermal conductivity and energy storage capacity[J]. Applied Energy,2018,211:1203-1215. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.025

[46] LV Y F, SITU W F, YANG X Q, et al. A novel nanosilica-enhanced phase change material with anti-leakage and anti-volume-changes properties for battery thermal management[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2018,163:250-259. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.02.061

[47] HUANG Q Q, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Pouch lithium battery with a passive thermal management system using form-stable and flexible composite phase change materials[J]. ACS Applied Energy Materials,2021,4(2):1978-1992. DOI: 10.1021/acsaem.0c03116

[48] WU W F, YE G H, ZHANG G Q, et al. Composite phase change material with room-temperature-flexibility for battery thermal management[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal,2022,428:131116. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131116

[49] LI S J, DONG X L, LIN X D, et al. Flexible phase change materials obtained from a simple solvent-evaporation method for battery thermal management[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2021,44:103447. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2021.103447

[50] LIN X W, ZHANG X L, LIU L, et al. Polymer/expanded graphite-based flexible phase change material with high thermal conductivity for battery thermal management[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production,2022,331:130014. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130014

[51] HUANG Q Q, DENG J, LI X X, et al. Experimental investigation on thermally induced aluminum nitride based flexible composite phase change material for battery thermal management[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2020,32:101755. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2020.101755

[52] CAO J H, WU Y, LING Z Y, et al. Upgrade strategy of commercial liquid-cooled battery thermal management system using electric insulating flexible composite phase change materials[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2021,199:117562. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.117562

[53] HUANG Q Q, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Flexible composite phase change material with anti-leakage and anti-vibration properties for battery thermal management[J]. Applied Energy,2022,309:118434. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118434

[54] WU W X, LIU J Z, LIU M, et al. An innovative battery thermal management with thermally induced flexible phase change material[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2020,221:113145. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113145

[55] HUANG Q Q, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Thermal management of lithium-ion battery pack through the application of flexible form-stable composite phase change materials[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2021,183:116151. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116151

[56] RONG H Q, WANG C H, LIU X Q, et al. A novel elastomeric copolymer-based phase change material with thermally induced flexible and shape-stable performance for prismatic battery module[J]. International Journal of Thermal Sciences,2022,174:107435. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2021.107435

[57] HUANG Y H, CHENG W L, ZHAO R. Thermal management of Li-ion battery pack with the application of flexible form-stable composite phase change materials[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2019,182:9-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.12.064

[58] ZHANG Y F, HUANG J H, CAO M, et al. A novel flexible phase change material with well thermal and mechanical properties for lithium batteries application[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2021,44:103433. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2021.103433

[59] HUANG Y H, CHENG Y X, ZHAO R, et al. A high heat storage capacity form-stable composite phase change material with enhanced flame retardancy[J]. Applied Energy,2020,262:114536. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114536

[60] NIU J Y, DENG S Y, GAO X N, et al. Experimental study on low thermal conductive and flame retardant phase change composite material for mitigating battery thermal runaway propagation[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2022,47:103557. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2021.103557

[61] WENG J W, XIAO C R, OUYANG D X, et al. Mitigation effects on thermal runaway propagation of structure-enhanced phase change material modules with flame retardant additives[J]. Energy,2022,239:122087. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122087

[62] LI L, XU C S, CHANG R Z, et al. Thermal-responsive, super-strong, ultrathin firewalls for quenching thermal runaway in high-energy battery modules[J]. Energy Storage Materials,2021,40:329-336. DOI: 10.1016/j.ensm.2021.05.018

[63] HUANG Q Q, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Innovative thermal management and thermal runaway suppression for battery module with flame retardant flexible composite phase change material[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production,2022,330:129718. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129718

[64] ZHANG J Y, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Experimental investigation of the flame retardant and form-stable composite phase change materials for a power battery thermal management system[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2020,480:229116. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2020.229116

[65] DAI X Y, KONG D P, DU J, et al. Investigation on effect of phase change material on the thermal runaway of lithium-ion battery and exploration of flame retardancy improvement[J]. Process Safety and Environmental Protection,2022,159:232-242. DOI: 10.1016/j.psep.2021.12.051

[66] YIN G Z, YANG X M, HOBSON J, et al. Bio-based poly (glycerol-itaconic acid)/PEG/APP as form stable and flame-retardant phase change materials[J]. Composites Communications,2022,30:101057. DOI: 10.1016/j.coco.2022.101057

[67] ZHANG W C, QIU J Y, YIN X X, et al. A novel heat pipe assisted separation type battery thermal management system based on phase change material[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,165:114571. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114571

[68] ZHAO J T, LV P Z, RAO Z H. Experimental study on the thermal management performance of phase change material coupled with heat pipe for cylindrical power battery pack[J]. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science,2017,82:182-188. DOI: 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2016.11.017

[69] 曲捷. 三维脉动热管传热与流动特性研究[D]. 徐州: 中国矿业大学, 2021. QU Jie. Study on the heat transfer and flow characteristics of three-dimensional oscillating heat pipe[D]. Xuzhou: China University of Mining and Technology, 2021(in Chinese).

[70] PUTRA N, SANDI A F, ARIANTARA B, et al. Performance of beeswax phase change material (PCM) and heat pipe as passive battery cooling system for electric vehicles[J]. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering,2020,21:100655. DOI: 10.1016/j.csite.2020.100655

[71] ABBAS S, RAMADAN Z, PARK C W. Thermal performance analysis of compact-type simulative battery module with paraffin as phase-change material and flat plate heat pipe[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2021,173:121269. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121269

[72] ALI H M. An experimental study for thermal management using hybrid heat sinks based on organic phase change material, copper foam and heat pipe[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2022,53:105185. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2022.105185

[73] LENG Z Y, YUAN Y P, CAO X L, et al. Heat pipe/phase change material thermal management of Li-ion power battery packs: A numerical study on coupled heat transfer performance[J]. Energy,2022,240:122754. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122754

[74] HUANG Q Q, LI X X, ZHANG G Q, et al. Experimental investigation of the thermal performance of heat pipe assisted phase change material for battery thermal management system[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2018,141:1092-1100. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.06.048

[75] QU J, KE Z Q, ZUO A, et al. Experimental investigation on thermal performance of phase change material coupled with three-dimensional oscillating heat pipe (PCM/3D-OHP) for thermal management application[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2019,129:773-782. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.10.019

[76] FENG L Y, ZHOU S, LI Y C, et al. Experimental investigation of thermal and strain management for lithium-ion battery pack in heat pipe cooling[J]. Journal of Energy Storage,2018,16:84-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2018.01.001

[77] 王烨. 基于平板热管——相变材料复合传热系统的动力电池热管理研究 [D]. 大连: 大连理工大学, 2021. WANG Ye. Study on a composite power battery thermal management system based on flat heat pipe-phase change material[D]. Dalian: Dalian University of Technology, 2021(in Chinese).

[78] YANG W, ZHOU F, LIU Y C, et al. Thermal performance of honeycomb-like battery thermal management system with bionic liquid mini-channel and phase change materials for cylindrical lithium-ion battery[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2021,188:116649. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116649

[79] HEKMAT S, MOLAEIMANESH G R. Hybrid thermal management of a Li-ion battery module with phase change material and cooling water pipes: An experimental investigation[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,166:114759. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114759

[80] MEHRABI-KERMANI M, HOUSHFAR E, ASHJAEE M. A novel hybrid thermal management for Li-ion batteries using phase change materials embedded in copper foams combined with forced-air convection[J]. International Journal of Thermal Sciences,2019,141:47-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2019.03.026

[81] LV Y F, LIU G J, ZHANG G Q, et al. A novel thermal management structure using serpentine phase change material coupled with forced air convection for cylindrical battery modules[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2020,468:228398. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2020.228398

[82] AKBARZADEH M, JAGUEMONT J, KALOGIANNIS T, et al. A novel liquid cooling plate concept for thermal management of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2021,231:113862. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2021.113862

[83] MASHAYEKHI M, HOUSHFAR E, ASHJAEE M. Development of hybrid cooling method with PCM and Al2O3 nanofluid in aluminium minichannels using heat source model of Li-ion batteries[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2020,178:115543. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115543

[84] LAZRAK A, FOURMIGUÉ J F, ROBIN J F. An innovative practical battery thermal management system based on phase change materials: Numerical and experimental investigation[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2018,128:20-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.08.172

[85] CAO J H, LUO M Y, FANG X M, et al. Liquid cooling with phase change materials for cylindrical Li-ion batteries: An experimental and numerical study[J]. Energy,2020,191:116565. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.116565

[86] KONG D P, PENG R Q, PING P, et al. A novel battery thermal management system coupling with PCM and optimized controllable liquid cooling for different ambient temperatures[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2020,204:112280. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112280

[87] ZHAO Y Q, ZOU B Y, LI C, et al. Active cooling based battery thermal management using composite phase change materials[J]. Energy Procedia,2019,158:4933-4940. DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.01.697

[88] SANTHANAGOPALAN S, GUO Q, RAMADASS P, et al. Review of models for predicting the cycling performance of lithium-ion batteries[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2006,156:620-628. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.05.070

[89] NING G, POPOV B N. Cycle life modeling of lithium-ion batteries[J]. Journal of Electrochemical Society,2004,151:A1584. DOI: 10.1149/1.1787631

[90] YANG Y T. Numerical simulation of three-dimensional transient cooling application on a portable electronic device using phase change material[J]. International Journal of Thermal Sciences,2011,51:155-162.

[91] LING Z Y, CHEN J J, FANG X M, et al. Experimental and numerical investigation of the application of phase change materials in a simulative power batteries thermal management system[J]. Applied Energy,2014,121:104-113. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.01.075

[92] GRECO A, CAO D P, JIANG X, et al. A theoretical and computational study of lithium-ion battery thermal management for electric vehicles using heat pipes[J]. Journal of Power Sources,2014,257:344-355. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.02.004

[93] YANG Y, CHEN L, YANG L J, et al. Numerical study of combined air and phase change cooling for lithium-ion battery during dynamic cycles[J]. International Journal of Thermal Sciences,2021,165:106968. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2021.106968

[94] CHEN K, HOU J S, SONG M X, et al. Design of battery thermal management system based on phase change material and heat pipe[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2021,188:116665. DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116665

[95] JIN X R, DUAN X T, JIANG W J, et al. Structural design of a composite board/heat pipe based on the coupled electro-chemical-thermal model in battery thermal management system[J]. Energy,2021,216:119234. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.119234

[96] BERNARDI D, PAWLIKOWSKI E, NEWMAN J. A general energy balance for battery systems[J]. Journal of Electrochemical Society,1985,132(1):5-12. DOI: 10.1149/1.2113792

[97] WANG R, LIANG Z, SOURI M, et al. Numerical analysis of lithium-ion battery thermal management system using phase change material assisted by liquid cooling method[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,2022,183:122095. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122095

[98] YI F, E J Q, ZHANG B, et al. Effects analysis on heat dissipation characteristics of lithium-ion battery thermal management system under the synergism of phase change material and liquid cooling method[J]. Renewable Energy,2022,181:472-489. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.09.073

-

期刊类型引用(4)

1. 刘凯豹,戴宇成,刘昌会,赵佳腾. 相变材料/热管耦合储热技术在不同领域应用研究进展. 机械工程学报. 2024(18): 183-194 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 戴其华,陈静,洪明虎,邵安埼. 新能源汽车电池管理系统的优化策略研究. 汽车维修技师. 2024(22): 22-23 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 肖鑫,李传高,周俊杰,刘开宇,高采薇. 氮化硼强化聚乙二醇/膨胀石墨复合相变材料的制备与热性能. 东华大学学报(自然科学版). 2023(05): 26-32+40 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 雷震霆,郑凯,赵汝和,汤建庭,孙姣姣,张栋. 相变材料储热在通信基站节能中的应用进展. 功能材料. 2023(12): 12001-12011 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(6)

-

目的

新能源汽车的出现缓解了能源危机。而车辆行驶时电池的温升明显,电池的寿命周期缩短。有机类相变材料(PCM)以其高热能密度、合适相变范围以及优异可循环使用性成为高效而有前景的新能源汽车电池热管理策略,但在实用化过程中仍有相应不足之处应予以改善。本文从有机PCM实用物性不足出发,概括了目前复合有机PCM的制备及改进方向。

方法总结了近年来用于电池热管理(BTM)的有机PCM的研究进展,并建议必须从热物性角度提高热导率、力学角度提高柔韧度,化学角度提高阻燃能力对PCM改善,添加多维高导热材料(如碳材料、纳米金属、泡沫金属等)强化导热;添加共聚物(如聚乙烯、热塑性弹性体等)提高材料柔韧性;添加阻燃剂(如红磷、聚磷酸铵等)提高阻燃效果;分别改善了有机PCM的低导热、不易加工和热失控易燃现象。同时描述了有机PCM与热管、液冷、空冷等散热方式耦合后系统强化换热的效果,对电池组最高温度/最大温差改善做出系统比对。总结耦合热管时需要考虑不同热管排布;耦合液冷或空冷需要设计合适流道对有机PCM散热的有效增强。随后介绍了模拟仿真分析对有机PCM在电池热管理领域的验证及预测,包括不同耦合散热的影响因素及最佳使用工况的研究。

结果1.1、热导率的增强最有效的方法是与膨胀石墨混合或浸渍到泡沫金属中。含量20%EG的复合PCM的热导率可达1.9~12.4 W·m·K,优于其他碳材料。虽然浸渍到泡沫金属中的PCM的导热系数可以提高10倍以上,且形状也是固定的,但不能适应不同尺寸的电池。1.2、柔性PCM是为了保护电池,同时降低接触电阻而合成的。因此,将共聚物添加到有机PCM中,复合柔性PCM的拉伸/弯曲强度通常可以小于1 MPa。而且大多数柔性PCM在高温下具有更好的灵活性,但不利于延长电池寿命。1.3、由于大多数有机PCM易燃,不利于BTM系统。将市售阻燃剂添加到相变材料中进行改进,将其极限氧指数(LOI)提高到26%~56.3%,峰值热释放率(HRR)不同程度地降低,从15.2%降低到73.1%。然而热失控(TR)的峰值温度仍在364~764 ℃对乘客造成伤害的高温范围内 ,但由于TR的发生推迟,乘客有可能疏散。2.1、PCM耦合热管散热优化:即便PCM的物理性能得到了改善,但远离相变点后,使用PCM的散热能力就会严重降低,因此必须耦合传统的散热方法。与仅使用热管或PCM的单一方法温降为1.4~8.5 ℃相比,最高温降可达6.3~9.3 ℃。不同的热管结构和布置引起的散热差异是明显的,应将其作为优化BTM系统的重要因素。2.2、PCM耦合液冷或风冷散热优化:对于与液体冷却相结合的系统,当不同的放电速率为2 C或5 C时,与单一液体冷却系统相比,最高温度降低约8 ℃。与单一PCM系统相比,温降更为明显,范围从2 ~14 ℃,这表明耦合液体冷却模式受管道和流量的影响很大。BTM系统耦合空气冷却也需要设计不同的空气通道来增强空气与PCM之间的对流换热。与单一PCM系统相比,耦合空气冷却后的系统最高温度为25.6 ~51.9 ℃,温度降低最高可达17 ℃。3、耦合系统仿真:为了进一步分析与热管、液体冷却或空气冷却耦合的BTM系统的优化,使用模拟可更深入地反映内部温度变化,这有助于有效评估BTM在复杂工况下的效果,同时获得更好的冷却条件。

目的描述了目前有机PCM用于电池热管理的进展及不足,其难点仍在于复合柔性PCM其可燃和导热性的改善,虽然可塑性强,但在室温下柔韧性不足;复合阻燃PCM能有效延缓热失控和抑制燃烧,但无法彻底解决其燃烧问题。针对PCM散热的局限介绍了热管、液冷、空冷与PCM的耦合系统的强化换热应用,仿真模拟对实验的验证延拓,有机PCM耦合传统散热系统的车载可靠性和循环可行性也缺乏相应探讨,为今后有机PCM用于BTM提出一定建议。

-

有机类相变材料(PCM)以其高热能密度、合适相变范围以及优异可循环使用性成为高效而有前景的新能源汽车电池热管理策略,但在实用化过程中仍有相应不足之处应予以改善。

本文从有机PCM实用物性不足出发,概括了目前复合有机PCM的制备及改进方向:添加多维高导热材料以提高热导率;添加高分子共聚物提高柔韧性;添加化学阻燃剂提高阻燃效果,分别改善了有机PCM低导热、不易加工和热失控易燃现象。同时进一步基础上评价了其与热管、液冷、空冷等散热方式耦合后对电池热管理系统强化散热效果,对电池组最高温度/最大温差改善做出系统比对。指出耦合热管散热方式,仍主要讨论形状各异的热管排布;耦合液冷和空冷的散热方式其研究侧重对不同液体和气体流道对有机PCM散热的有效增强。最后介绍了模拟仿真分析对有机PCM在电池热管理领域的验证及预测,包括不同耦合散热的影响因素及最佳使用工况的研究。

最后总结了目前有机PCM用于电池热管理的进展及不足,其难点仍在于复合柔性PCM虽然可塑性强,但在室温下柔韧性不足;复合阻燃PCM能有效延缓热失控和抑制燃烧,但无法彻底解决其燃烧问题。有机PCM耦合传统散热系统的车载可靠性和循环可行性也缺乏相应探讨,为今后有机PCM用于电池热管理提出一定建议。

Comparison of reduction of peak HRR when TR occurs with different flame retardants[59,61,63-66]

下载:

下载: