Research progress on biomass and biomass-related hemostatic materials

-

摘要:

伤口的快速止血和愈合对于解决意外事故造成的出血具有重要意义,相关止血材料的开发和应用一直备受关注。以角蛋白、丝素蛋白、胶原蛋白为代表的蛋白类和以纤维素、壳聚糖、海藻酸为代表的多糖类等生物质材料,因其无毒性、低抗原性、良好的生物相容性、生物可降解性等优点在止血领域展现了前所未有的应用价值。基于此,本文对生物质止血材料的设计、制备及止血应用的最新研究进展进行了全面综述,并对其发展前景做了展望,以期为新型高效止血材料的开发和实际应用提供思路。

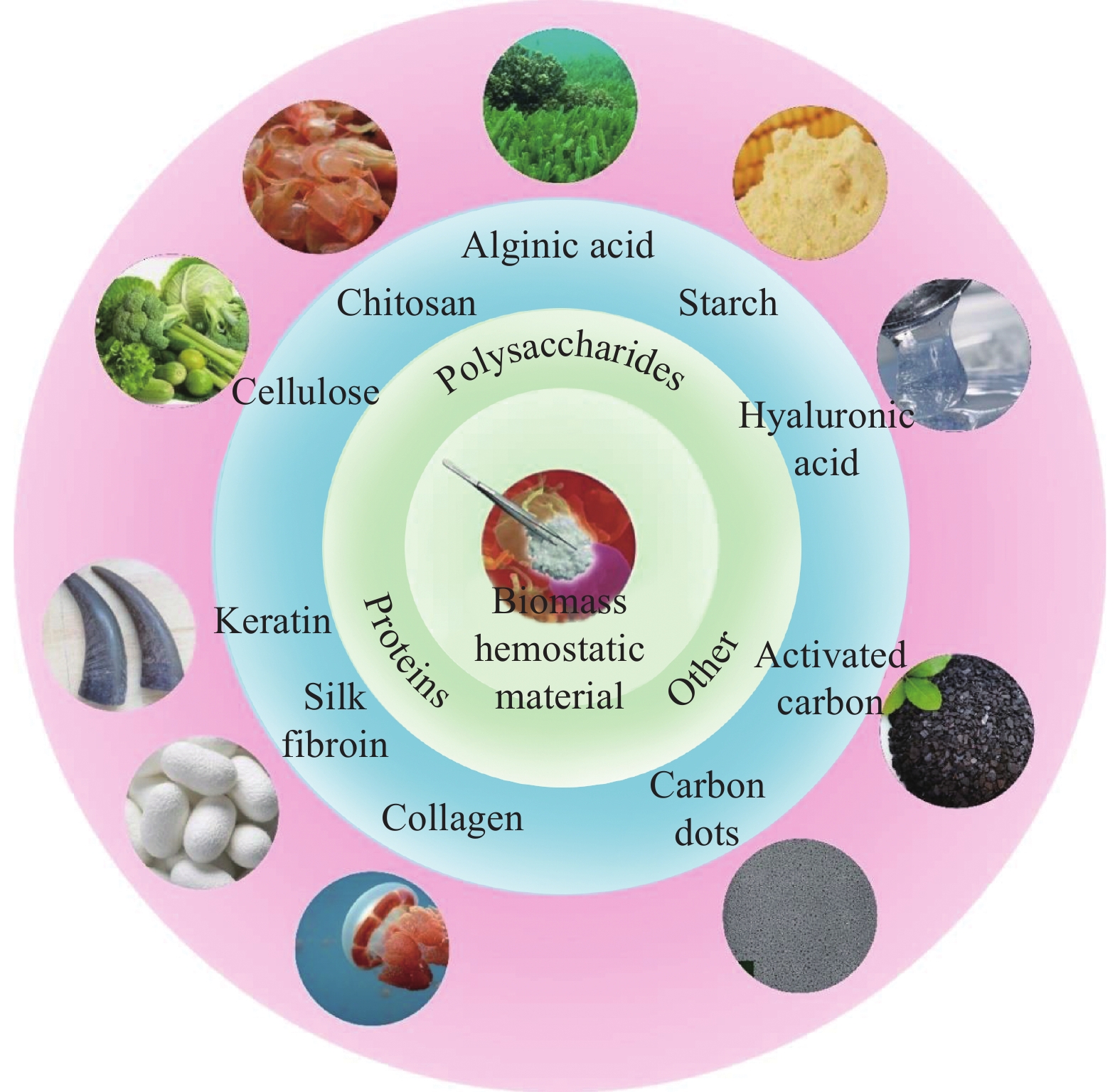

Abstract:The rapid hemostasis and healing of wounds after trauma hold great significance to solve the bleeding caused by accidents. Therefore, the development and application of related hemostatic materials have attracted much attention. Biomass-derived materials such as proteins including keratin, silk fibroin, collagen and polysaccharides including cellulose, chitosan, and alginic acid are favored by researchers because of their non-toxicity, low antigenicity, good biocompatibility, and biodegradability, and have shown unprecedented application value in the field of hemostasis. In this paper, the latest research results on the design, the preparation and the application of biomass hemostatic materials are comprehensively reviewed, and their development prospects are prospected, which will provide ideas for the development and practical application of new high-efficiency hemostatic materials.

-

Keywords:

- biomass materials /

- protein /

- polysaccharide /

- hemostasis properties /

- wound hemostasis

-

随着全球能源结构的转型和对清洁能源需求的不断增长,氢能作为一种清洁、高效的能源载体,正逐渐成为新能源领域的研究热点[1-3]。然而,氢能的高效储存和运输是实现其广泛应用的关键技术挑战之一。在众多储氢技术中,纤维缠绕复合材料高压储氢技术因技术成熟度和成本优势,被广泛应用于航空航天和交通运输领域[4-7]。复合材料缠绕层作为载荷承担的主体,是决定气瓶结构承载能力和安全性的重要因素。爆破压力是高压储氢容器设计的关键指标之一。为提高复合压力容器的结构效率,降低储氢成本,通常在设计阶段使用有限元方法对缠绕结构的爆破行为进行分析并对缠绕层进行优化。目前储氢气瓶的有限元分析中,直接将气瓶缠绕层看作不同角度纤维层的堆叠,基于层合结构数值模型对纤维缠绕储氢气瓶的结构性能进行评估[8-10]。但纤维束在螺旋缠绕过程中会产生交叉起伏,直接采用层合数值模型难以考虑交叉起伏形态特征对缠绕层力学性能的影响[11-15],影响爆破压力预测结果的准确性。

已有研究发现纤维束的交叉起伏会降低复合材料的力学性能[16-18]。Shen等[19]建立了一种介观模型来研究纤维交叉起伏对缠绕复合材料刚度的影响,证明了纤维交叉起伏会产生显著影响纤维缠绕复合材料(Filament-wound composites,FWC)的弹性参数。Shen提出,缠绕纤维束厚度也是影响力学性能的一个关键因素。Henry等[20]研究了纤维缠绕圆筒在压缩载荷下损伤行为,发现纤维起伏会降低纤维缠绕圆筒的压缩强度。Chang等[21]研究了缠绕圆筒在拉伸、扭转和多轴载荷下的损伤响应,结果表明纤维损伤首先出现在缠绕交叉起伏区域,并沿此区域扩展。Chang等[22]进一步建立缠绕圆筒全尺寸模型,基于缠绕特征区域赋予材料属性,结果证明这种模型可以模拟缠绕圆筒的损伤过程。Hameed等[23]提出了一种模拟缠绕图案特征的压力容器分区建模方法。与传统的有限元模型相比,该模型可以捕捉缠绕图案对应变分布的影响。Arellano等[24]则采用数字图像相关技术(DIC)对缠绕平板应变分布进行了监测,验证了分区建模方法的合理性。在此基础上,肖磊等[25]使用数值仿真和实验手段相结合的方法进一步对比了FWC平板和标准层合复合材料(Standard laminate composites,SLC)平板的应变分布,结果证明缠绕结构菱形特征图案中部纤维交叉起伏区域存在明显的应变集中现象,是导致该区域损伤起始的主要原因。

在复合材料气瓶结构设计中,有限元分析是常用的手段之一[26]。当前报道的建模类型包括轴对称模型[11]和三维模型[15]两大类。根据Lekhnitskii假设[27],材料围绕一个轴是对称的,使用轴对称模型不会影响爆破压力结果,并且可以有效提高计算效率[28]。相比轴对称模型,三维模型可以考虑纤维缠绕变角度等特征,开展基于三维尺度的水压爆破和低速冲击分析[29-30],可提供更高的分析精度。三维壳单元模型通过在壳结构上定义复合材料厚度和方向模拟气瓶结构[31-35],从而降低气瓶建模的难度。壳单元在建模难度和计算效率上具有优势[36-38],但三维实体单元[39-42]更能反映缠绕层的几何特征,更适合于精确计算和捕捉复合材料层间的损伤行为。为了研究结构失效机制,许多损伤失效模型被应用在气瓶有限元分析中,包括Hashin失效准则[43]、Puck失效准则[31]、Hashin–Rottem失效准则[35]等。为了提高三维实体模型的计算效率,减少结构模型的尺寸,借助周期性边界条件,建立气瓶的1/4[44]、1/12[8]和1/72[39]模型,是当前常用的有效手段。

在已有的文献报道中,气瓶多基于简化的轴对称模型和三维模型,将缠绕层假设为层合结构进行分析,忽略了纤维缠绕结构中的纤维交叉起伏对纤维方向强度的影响。但对缠绕结构的研究已经表明,纤维交叉起伏会影响缠绕结构的力学性能。因此在复合材料气瓶结构分析中,忽略纤维交叉起伏影响会减低预测精度,难以准确分析缠绕结构的失效模式和强度。虽然通过建立包含纤维束形态的气瓶介观模型,可以直接考虑纤维束交叉起伏特征,但与平板模型和圆筒模型相比,气瓶模型更为复杂,在复合材料气瓶结构分析中使用该方法会显著增加建模难度,并降低计算效率。

为了评估纤维束介观交叉起伏形态的影响,实现气瓶爆破行为的准确预测,并兼顾计算效率,本文提出一种考虑纤维强度折减效应对气瓶层合模型进行修正的爆破失效分析方法(折减分析方法),并与不考虑纤维强度折减效应的爆破失效分析方法(传统分析方法)进行了对比。首先,采用实验和数值模拟相结合的方法研究纤维交叉起伏特征对缠绕平板拉伸行为的影响机制,探索缠绕参数对纤维拉伸强度的影响规律。然后,通过对传统层合模型分析方法中各角度缠绕层纤维方向拉伸强度进行修正,发展了一种考虑纤维交叉起伏影响的Ⅳ型气瓶爆破行为预测数值分析方法。最后,分别使用折减分析方法和传统分析方法,开展3种不同铺层Ⅳ型气瓶的爆破失效分析,并与对应铺层的气瓶水压爆破试验结果进行对比,验证本文提出的Ⅳ型气瓶爆破失效分析方法的准确性。

1. 纤维强度折减效应研究

在纤维螺旋缠绕过程中,会形成一个以纤维交叉起伏为特征的区域,如图1所示。由纤维交叉引起的纤维束起伏可能会影响复合材料的拉伸强度。纤维强度折减效应研究选择了一个含纤维交叉起伏的特征区域作为研究对象,制备了纤维缠绕的FWC平板试样,用来模拟典型的纤维束交叉起伏特征。同时制备了相同角度的标准层合结构的SLC平板试样作为对照组。沿纤维的+α°方向,对两类试样进行了单向拉伸的实验和仿真的对比分析,获得纤维交叉起伏结构的强度折减规律。

1.1 实 验

首先进行FWC平板和SLC平板试样制备。如图2所示,将预浸料裁成长400 mm、宽6 mm的预浸带,模拟缠绕过程交叉铺贴获得缠绕平板,铺贴过程不考虑张力作用,采用真空袋压法制备了4组缠绕角度为±10°、±20°、±30°和±40°的FWC平板试样。作为对比,制备了4组相同角度的SLC平板试样。试样整体厚度为0.43 mm,共两层,其中试样长度方向沿着+α°纤维束方向,实际平板试样的纤维束夹角为2α°。

在电子万能试验机(LD23.104,力试科学仪器有限公司)上对试样进行拉伸试验,参考标准ASTM D3039[45]进行加载,并使用DIC设备(Vic-2D,Correlated Solutions Europe)监测加载过程中试样表面的位移场和应变场,如图3所示。为确保DIC方法监测应变场的准确性,在试验前先对试样表面进行散斑喷涂。然后进行试样和设备安装,在加载过程中设置拍摄频率为1 Hz,拉伸位移速度为2 mm/min。拉伸载荷通过试验机传感器获得,实际位移通过DIC的非接触式引伸计获得。

1.2 有限元分析

基于ABAQUS/Explicit求解器建立了三维有限元模型,采用Hashin失效起始准则和渐进损伤演化方式模拟FWC平板和SLC平板试样的拉伸失效行为。为了在模型中准确建立纤维交叉起伏的细节特征,使用光学显微镜拍摄并测量了不同缠绕角度下FWC平板试样截面参数,如图4(a)所示。将测量的起伏角度作为评估缠绕结构起伏特征的关键参数。同时为了建立双层厚度的纤维缠绕结构平板模型,进行缠绕层厚度对纤维折减系数影响的研究,进一步制备了双层厚度的缠绕结构试样,并测量了这些试样交叉区域的起伏角度,如图4(b)所示。图4(c)、图4(d)为单层和双层FWC试样的纤维起伏角度随缠绕角度的变化规律,单层厚度试样平均起伏角度分别为7.6°、7.7°、8.1°和8.6°,双层厚度试样的平均起伏角度分别为9.7°、10.6°、11.2°和12.5°。

在Abaqus有限元软件中建立了FWC平板和SLC平板的有限元模型。SLC平板的有限元模型和边界条件设置如图5所示,在左侧加载区域的上下表面施加固定约束,在右侧加载区域施加位移加载,加载速率与试验一致。样品的拉伸区域长度为100 mm,为了避免边界处的应力集中导致样品过早失效,在拉伸区域的左侧和右侧各7 mm长度区域内未设置材料失效,而在拉伸区域中间的86 mm长度区域内考虑了材料失效。

根据显微镜观察到的FWC平板试样截面交叉起伏几何特征,建立了FWC平板试样的细节模型,如图6所示。模型中的纤维起伏角度与测量的纤维起伏平均角度相同,在交叉起伏边缘和纤维束之间的间隙存在,并使用树脂对这些间隙进行了填充。图7为建立的FWC平板的有限元模型,边界条件和加载方式与试验保持一致。在FWC平板左侧宽50 mm区域上下表面施加固定约束,在FWC平板右侧宽50 mm区域上下表面设置向右的拉伸位移载荷,加载速率与试验一致。为避免边界应力集中导致样品过早失效,试样中间宽86 mm区域的复合材料设置了材料失效,两侧7 mm区域未设置材料失效。

单向纤维束材料参数的弹性模量、泊松比和极限强度等参数通过试验测试获得,试验测试参考ASTM测试标准[45-49],详见表1。

表 1 单向纤维束材料参数Table 1. Material properties of unidirectional fiber bundleItems Value Longitudinal modulus, E11/GPa 125.4 Transverse modulus, E22 =E33/GPa 7.7 In-plane shear modulus, G12=G13/GPa 3.8 Out-of-plane shear modulus, G23/GPa 4.8 Major Poisson's ratio, μ12 = μ13 0.33 Through-thickness Poisson's ratio, υ23 0.35 Longitudinal tensile strength, XT/GPa 2.18 Longitudinal compressive strength, XC/GPa 1.2 Transverse tensile strength, YT/MPa 60 Transverse compressive strength, YC/MPa 140 Density of laminate, ρ/(kg·m−3) 1600 Tensile fracture energy of fiber, Gft/(N·mm−1) 133 Compressive fracture energy of fiber, Gfc/(N·mm−1) 40 Tensile fracture energy of matrix, Gmt/(N·mm−1) 0.6 Compressive fracture energy of matrix,Gmc/(N·mm−1) 2.1 Elastic modulus of resin, E/GPa 3.0 Density of resin, ρr/(kg·m−3) 1200 Poisson's ratio of resin, μ 0.3 采用Hashin失效准则对纤维和基体的起始损伤进行判定,采用基于能量的线性本构描述材料损伤起始后的演化行为。平板拉伸失效分析和气瓶的爆破分析采用相同的失效准则,如下式:

纤维拉伸失效(σ11 > 0):

(σ11XT)2⩾ (1) 纤维压缩失效(σ11 < 0):

{\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{11}}{{X}_{\mathrm{C}}}\right)}^{2}\geqslant 1 (2) 基体拉伸失效(σ22 > 0):

{\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{22}}{{X}_{\mathrm{T}}}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{12}}{{S}_{12}}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{({\sigma }_{23}{)}^{2}+{\sigma }_{22}{\sigma }_{23}}{{S}_{23}}\right)}^{2}\geqslant 1 (3) 基体压缩失效(σ22 < 0):

\left(\frac{\sigma_{22}}{S_{22}}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sigma_{22}+\sigma_{33}}{Y_{\mathrm{C}}}\right)\left(\left(\frac{Y_{\mathrm{C}}}{2S_{23}}\right)^2-1\right)+ \quad \frac{({\sigma }_{23}^{2}-{\sigma }_{22}{\sigma }_{23})}{{S}_{23}^{2}}+{\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{12}}{{S}_{12}}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{13}}{{S}_{13}}\right)}^{2}\geqslant 1 (4) 面内损伤演化:

{d}_{i}=\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}\left\{0,\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\left\{1,{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{\mathrm{f}}\frac{{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}-{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{0}}{{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}({\mathrm{\varepsilon }}_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{\mathrm{f}}-{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{0})}\right\}\right\} (5) 其中:XT、XC分别为纤维方向拉伸和压缩强度;YC为垂直于纤维方向压缩强度;S22为垂直于纤维方向拉伸强度;S12、S13、S23为剪切强度;σ11、σ22分别为纤维方向和垂直于纤维方向的正应力;σ12、σ13和σ23为剪切应力; {\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{0} 为复合材料结构失效起始状态下的等效应变; {\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}}^{\mathrm{f}} 为复合材料结构完全失效状态下的等效应变; {\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{e}\mathrm{q}} 为复合材料结构当前状态下的等效应变[50]。

1.3 结果对比与分析

图8为0.43 mm厚度4组不同缠绕角的FWC平板和SLC平板拉伸实验的位移-载荷曲线。在加载过程中加强片和试件之间会发生滑动,为了使位移值更接近实际值,位移值使用DIC系统的电子引伸计功能测量,载荷值采用试验机记录的加载力。从图中发现,FWC平板的极限强度低于相同角度的SLC平板试件,FWC平板的承载能力显著降低。与相同角度的SLC平板对比,FWC平板刚度分别降低了3.70%、2.93%、1.50%和0.55%,均小于5.00%。FWC平板刚度降低并不明显,因此本文重点讨论纤维强度折减效应。

图9和图10分别为实验和有限元分析中得到的FWC平板和SLC平板的长度方向应变场(εyy)。两者结果相比,FWC平板的实验和模拟应变场都表现出应变集中。相反,SLC平板的应变场没有显示出应变集中,尽管位移增加,SLC平板的表面应变保持着相对均匀的分布。有限元与实验的表面应变结果具有良好的一致性。

图11为两种平板各角度仿真(FEA)和实验(EXP)的位移-载荷曲线及FWC平板的纤维拉伸失效云图。结果表明,仿真与实验所得的平板拉伸刚度高度一致,且在拉伸极限强度方面的误差较小,这验证了数值分析与实验结果之间具有很好的一致性。右侧云图为FWC平板纤维拉伸失效过程仿真结果。图11中载荷达到 a点时,FWC平板少数单元应力水平达到纤维拉伸起始失效判据,单元开始失效,单元刚度出现退化;随着继续载荷达到b点,失效面积逐渐扩展;最终加载至c点,缠绕交叉区域多数单元完全失效,FWC平板失去承载能力。

![]() 图 11 仿真和实验位移-载荷曲线和FWC平板纤维拉伸失效演化:(a) ±10°;(b) ±20°;(c) ±30°;(d) ±40°dft—Variable of fiber tensile failure state; FEA—Simulation; EXP—ExperimentFigure 11. Simulation and experimental displacement-load curves and the evolution of fiber tensile failure in FWC plate: (a) ±10°; (b) ±20°; (c) ±30°; (d) ±40°

图 11 仿真和实验位移-载荷曲线和FWC平板纤维拉伸失效演化:(a) ±10°;(b) ±20°;(c) ±30°;(d) ±40°dft—Variable of fiber tensile failure state; FEA—Simulation; EXP—ExperimentFigure 11. Simulation and experimental displacement-load curves and the evolution of fiber tensile failure in FWC plate: (a) ±10°; (b) ±20°; (c) ±30°; (d) ±40°图12为

4000 N载荷下FWC平板+α°层拉伸方向应变云图和纤维方向应力云图。可知,当载荷均为4000 N时,FWC平板在纤维交叉起伏区域均出现了明显的应变集中和应力集中现象,且随着缠绕角度的增大,应变集中和应力集中效果越明显,拉伸方向最大应变从0.0127 增加到0.0143 ,纤维方向最大应力从1713 MPa增加到1986 MPa。同时,应变集中和应力集中的区域与纤维起伏的区域重合。据此可知,+α°层的起伏是导致应变集中和应力集中产生的原因,使纤维过早达到其极限拉伸强度,进而导致FWC平板的承载能力下降。缠绕角度增加,纤维起伏角度越大,承载能力下降效果越明显,纤维强度折减效应越显著。由此分析,当相同角度缠绕层厚度增加时,纤维起伏角度也会增加,并使承载能力进一步下降,纤维强度折减效应更加显著。1.4 纤维强度折减系数

图13为有限元分析两种厚度试样的拉伸失效载荷结果。可以发现,所有FWC平板的拉伸失效载荷都低于对应的SLC平板。定义FWC平板与SLC平板的最大失效载荷之比为纤维强度折减系数,则纤维强度折减系数的变化规律如图14所示。单层板的不同缠绕角度的强度折减系数分别为0.93、0.91、0.90和0.89。双层平板不同缠绕角度的纤维强度折减系数分别为0.80、0.78、0.70和0.68。随着缠绕角度变大,强度折减系数逐渐降低。同时缠绕层厚度的增加,相同缠绕角度的纤维强度折减系数也显著降低。

根据图14中的纤维强度折减系数随缠绕角度和厚度的变化规律,建立纤维强度折减系数随厚度和角度的线性拟合公式,如下式所示:

\kappa =\frac{({t}_{\mathrm{f}}-{t}_{2})}{({t}_{1}-{t}_{2})}({\kappa }_{1}-{\kappa }_{2})+{\kappa }_{2} (6) 式中:κ表示纤维强度折减系数;t1和t2表示本文中使用的单层和双层预浸料的厚度;tf表示缠绕单层的厚度; {\kappa }_{1} 和 {\kappa }_{2} 的表示式分别为: {\kappa }_{1} =0.94−

0.0013 α和 {\kappa }_{2} =0.85−0.0044 α;α表示当前的缠绕角度。当缠绕制品的纤维束带宽为6 mm,缠绕螺旋层厚度在0.4~0.8 mm,缠绕角度范围在±10°~±40°之间,可以使用式(6)对纤维拉伸强度进行折减分析。本文的气瓶数值分析中,使用该经验公式对气瓶不同缠绕层的拉伸强度进行折减,开展进一步的气瓶爆破失效分析,并与未考虑强度折减的分析方法进行了对比。

2. 基于纤维强度折减效应的气瓶数值分析

基于本文提出的纤维强度折减效应,对3种不同铺层的IV型气瓶进行爆破行为预测,分别使用不考虑纤维强度折减效应的传统分析方法和考虑纤维强度折减效应的折减分析方法对气瓶爆破压力和爆破失效位置进行数值分析预测。

图15为气瓶数值分析框架。在气瓶数值分析中,首先建立包含变厚度分层信息的气瓶三维模型,并对气瓶划分网格。然后计算缠绕层不同位置的变角度信息后,将角度信息赋予在模型网格上。随后将考虑纤维强度折减效应的VUMAT材料参数赋予在气瓶缠绕层几何模型上,并赋予内胆对应的材料属性,继续设置模型的接触属性和边界条件,最后提交计算进行气瓶的渐进损伤有限元分析。

2.1 铺层信息和材料参数

使用图16所示的9 L-IV型气瓶内胆进行铺层设计。筒身为高密度聚乙烯(HDPE)材料,两端金属封头(BOSS)为6061-T6铝合金材料。筒身长度400 mm,外径164 mm,厚度5 mm,采用椭圆形封头,长轴为82 mm,短轴为53 mm,极孔半径为23 mm。为了验证本文提出的折减分析方法在不同爆破失效模式下的预测精度和适用性,设计了3种不同铺层,铺层信息如下:

A:[±14°/±90°/±90°/±25°/±90°/±35°/±90°/±14°];

B:[±14°/±90°/±90°/±25°/±90°/±35°/±90°/±90°];

C:[±14°/±90°/±25°/±90°/±35°/±35°/±90°/±14°]。

螺旋层纤维方向拉伸强度XT取折减后对应强度值,一个循环的螺旋层厚度为0.5 mm,根据对纤维强度折减系数的经验公式计算,最终±14°、±25°及±35°螺旋缠绕层的纤维强度折减系数分别为0.90、0.88和0.86,对应折减后的螺旋层纤维拉伸强度分别为

2250 MPa、2200 MPa和2150 MPa。本文所用IV型气瓶材料中的复合材料缠绕层[51]、两端金属瓶口(BOSS)[52]和筒身高密度聚乙烯(HDPE)内胆[53]的材料属性如表2所示。表 2 IV型气瓶材料力学性能参数Table 2. Type IV cylinder material mechanical parametersItem Value Longitudinal modulus, E11/GPa 154 Transverse modulus, E22 =E33/GPa 11.4 In-plane shear modulus, G12=G13/GPa 4.8 Out-of-plane shear modulus, G23/GPa 3.8 Major Poisson's ratio, μ12 = μ13 0.3 Through-thickness Poisson's ratio, υ23 0.33 Longitudinal tensile strength, XT/GPa 2.5 Longitudinal compressive strength, XC/GPa 1.2 Transverse tensile strength, YT/MPa 70 Transverse compressive strength, YC/MPa 180 Density of laminate, ρ/(kg·m−3) 1600 Tensile fracture energy of fiber, Gft/(N·mm−1) 133 Compressive fracture energy of fiber, Gfc/(N·mm−1) 40 Tensile fracture energy of matrix, Gmt/(N·mm−1) 0.6 Compressive fracture energy of matrix,Gmc/(N·mm−1) 2.1 Elastic modulus of HDPE, E/GPa 1.1 Poisson's ratio of HDPE, μ 0.38 Yield strength of HDPE, σs/MPa 22.9 Ultimate strength of HDPE, σb/MPa 25 Fracture elongation of HDPE, δ/% >600 Elastic modulus of BOSS, E/GPa 69 Poisson's ratio of BOSS, μ 0.324 Yield strength of BOSS, σs/MPa 298 Ultimate strength of BOSS, σb/MPa 330 Fracture elongation of BOSS, δ/% 12 Note: BOSS—Bolted opening support structure. 2.2 模型与边界条件

建立气瓶的1/360模型,单元类型为C3D8R,模型共计

26318 个单元,如图17所示。在气瓶剖面施加周期性边界条件,根据气瓶爆破试验工况建立边界条件:在气瓶左侧接头处设置为沿轴向的固定约束,避免发生刚体位移;内胆的塑料部分和金属BOSS部分的接触属性设置为Tie,模拟两者之间的固定效果;内胆外表面与缠绕层内表面的接触属性设置为Tie,模拟两者之间的粘接效果。气瓶内表面施加100 MPa压力(P),基于Hashin失效准则进行分析,基于能量的线性本构描述材料损伤起始后的演化行为,实际爆破压力以缠绕层纤维贯穿损伤为判断依据。3. 气瓶制备与水压测试

为了验证两种预测方法的准确性,根据3种缠绕线型制备了对应的IV型气瓶,并进行了水压爆破测试。

制备过程如图18所示,采用湿法缠绕工艺,对IV型气瓶进行缠绕制备。内胆主体材料为高密度聚乙烯(High-density polyethylene,HDPE),BOSS材料为6061-T6铝合金。碳纤维缠绕层材料为光威TZ700-24 K级碳纤维增强树脂基复合材料,树脂为博汇EpoTech®425型环氧树脂。气瓶内胆使用滚塑工艺制成,通过滚塑模具将铝合金BOSS和聚乙烯内胆滚塑一体成型。根据湿法缠绕工艺要求,缠绕前先将树脂和固化剂按比例混合,倒入到胶槽中,纤维束经过胶槽滚轮浸润树脂后,连接到丝嘴位置,然后缠绕到瓶身位置。缠绕路径由一台六轴五联动数控缠绕机(SLW01.6-500-4/1-5000CNC,湖南江南四棱数控有限公司)控制,通过 CADWIND软件编写的环向缠绕和螺旋缠绕程序,将纤维束按照缠绕层顺序缠绕在气瓶表面。缠绕完成后,将气瓶安装到旋转固化炉中,按照树脂固化曲线设置温度,经固化成型后,得到碳纤维增强树脂基体(Carbon fiber reinforced polymer,CFRP)复合材料储氢气瓶试样。

如图19(a)所示,根据标准GB/T 15385—2022《气瓶水压爆破试验方法》[54],使用水压爆破试验机(EHM-8102,深圳市恩普达工业系统有限公司)对IV型气瓶进行爆破测试。爆破前首先将在气瓶内部灌满水并排除内部空气,防止在爆破瞬间内部空气造成的碎片飞溅,损坏试验设备或者危害人身安全。然后使用高压水管连接爆破试验机和气瓶,水管和气瓶之间使用转接头连接,用生胶带和橡胶圈保证密封性。将气瓶放置在钢筒中,防止爆破碎屑飞出。最后启动试验机,加压开始爆破测试。测试装置如图19(a)所示。

根据图19(b)~图19(d)爆破试验结果,A铺层气瓶的爆破压力为62.86 MPa,爆破位置在封头与筒身过渡的肩部,B铺层气瓶的爆破压力为49.21 MPa,爆破位置在BOSS区域,C铺层气瓶的爆破压力为52.95 MPa,爆破位置在筒身区域。

4. 结果与讨论

图20为气瓶爆破失效前纤维应力云图。图20(a)~图20(c)为传统分析方法的结果,图20(d)~图20(f)为折减分析方法的结果。对传统分析方法的结果进行分析,根据图20(a)可知,A气瓶在爆破失效前纤维方向最大应力出现在筒身段环向层位置,当内部压力加载至66.4 MPa,环向层纤维方向应力值达到

2493.36 MPa,接近环向层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。图20(b)中,B气瓶在爆破失效前纤维方向最大应力出现在靠近两端金属BOSS附近的最内层14°螺旋层,56.6 MPa压力下该位置纤维方向应力为2486.25 MPa,接近未折减14°螺旋层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。图20(c)中,C气瓶在爆破失效前纤维方向最大应力在筒身段环向层位置,压力达到53.0 MPa时,该位置纤维方向应力为2492.30 MPa,接近环向层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。![]() 图 20 气瓶爆破失效前纤维应力云图:(a) A铺层-传统分析方法;(b) B铺层-传统分析方法;(c) C铺层-传统分析方法;(d) A铺层-折减分析方法;(e) B铺层-折减分析方法;(f) C铺层-折减分析方法Figure 20. Fiber stress nephogram of cylinder before failure: (a) Layup A-traditional method; (b) Layup B-traditional method; (c) Layup C-traditional method; (d) Layup A-reduction modified method; (e) Layup B-reduction modified method; (f) Layup C-reduction modified method

图 20 气瓶爆破失效前纤维应力云图:(a) A铺层-传统分析方法;(b) B铺层-传统分析方法;(c) C铺层-传统分析方法;(d) A铺层-折减分析方法;(e) B铺层-折减分析方法;(f) C铺层-折减分析方法Figure 20. Fiber stress nephogram of cylinder before failure: (a) Layup A-traditional method; (b) Layup B-traditional method; (c) Layup C-traditional method; (d) Layup A-reduction modified method; (e) Layup B-reduction modified method; (f) Layup C-reduction modified method根据图20(d)~图20(f),对折减分析方法的结果进行分析。A气瓶在爆破失效前最大应力同样出现在筒身中部最内层的环向缠绕层,当内压达到57.6 MPa时,最大应力为

2156.69 MPa,未达到环向层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。对于B气瓶,在爆破失效前,压力达到52.0 MPa时,缠绕层纤维方向最大应力出现在金属BOSS附近最内层14°螺旋层,最大应力为2236.68 MPa,接近折减后14°螺旋层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。对于C气瓶,在爆破失效前,最大应力出现在筒身中部最内层的环向缠绕层,内压达到53.0 MPa,纤维方向最大应力为2492.30 MPa,接近环向层复合材料纤维拉伸强度。图21为气瓶爆破失效时纤维损伤云图,将纤维损伤贯穿缠绕层作为判断气瓶爆破失效的依据。其中图21(a)~图21(c)为传统分析方法的结果,图21(d)~图21(f)为折减分析方法的结果。对A气瓶进行分析,根据图21(a)、图21(d)结果发现,使用传统分析方法预测的爆破压力为68 MPa,爆破发生在筒身位置。使用折减分析方法预测A气瓶爆破压力为59.6 MPa,气瓶爆破发生在筒肩位置。对B气瓶进行分析,根据图21(b)、图21(e)结果发现,传统分析方法爆破压力为56.8 MPa,爆破发生在BOSS位置。使用折减分析方法,B气瓶爆破压力为52.2 MPa,爆破发生在BOSS位置。对C气瓶进行分析,根据图21(c)和图21(f)结果发现,两种方法的爆破压力都是56.4 MPa,爆破位置都位于筒身位置。和图19中水压爆破试验的结果对比,试验中A气瓶破坏位置在筒肩位置,和折减分析方法破坏位置相同,传统分析方法则破坏于筒身位置。试验中B气瓶破坏发生在BOSS位置,与两种分析方法预测的爆破位置相同。试验中C气瓶破坏发生在筒身位置,与两种分析方法预测的爆破位置相同。

表3给出了3种铺层气瓶的实验与仿真爆破压力和爆破失效位置的结果对比。从表中可以发现,对A气瓶,折减分析方法得到的爆破压力误差为5.19%,爆破位置预测正确;传统分析方法得到的爆破压力误差为8.18%,爆破位置预测错误。对B气瓶,折减分析方法得到的爆破压力误差为6.07%,爆破位置预测正确;传统分析方法得到的爆破压力误差为15.4%,爆破位置预测正确。对C气瓶,两种方法预测的结果相同,爆破压力误差均为6.52%,爆破位置预测正确。

![]() 图 21 气瓶爆破失效纤维拉伸损伤云图对比:(a) A铺层-传统分析方法;(b) B铺层-传统分析方法;(c) C铺层-传统分析方法;(d) A铺层-折减分析方法;(e) B铺层-折减分析方法;(f) C铺层-折减分析方法Figure 21. Comparison of fiber tensile failure nephogram of cylinder: (a) Layup A-traditional method; (b) Layup B-traditional method; (c) Layup C-traditional method; (d) Layup A-reduction modified method; (e) Layup B-reduction modified method; (f) Layup C-reduction modified method表 3 气瓶爆破失效结果对比Table 3. Comparison of burst failure results of cylinders

图 21 气瓶爆破失效纤维拉伸损伤云图对比:(a) A铺层-传统分析方法;(b) B铺层-传统分析方法;(c) C铺层-传统分析方法;(d) A铺层-折减分析方法;(e) B铺层-折减分析方法;(f) C铺层-折减分析方法Figure 21. Comparison of fiber tensile failure nephogram of cylinder: (a) Layup A-traditional method; (b) Layup B-traditional method; (c) Layup C-traditional method; (d) Layup A-reduction modified method; (e) Layup B-reduction modified method; (f) Layup C-reduction modified method表 3 气瓶爆破失效结果对比Table 3. Comparison of burst failure results of cylindersNumber Method Pressure/MPa Burst location Error/% A Test 62.86 Transition region − Traditional method 68.00 Cylinder body +8.18 Reduction modified method 59.60 Transition region −5.19 B Test 49.21 BOSS − Traditional method 56.80 BOSS +15.42 Reduction modified method 52.20 BOSS +6.07 C Test 52.95 Cylinder body − Traditional method 56.40 Cylinder body +6.52 Reduction modified method 56.40 Cylinder body +6.52 综合以上结果分析,对于A气瓶,使用传统分析方法预测时,其爆破预测位置在筒身段,各角度缠绕层强度相同,最大应力出现在筒身段。而考虑纤维强度折减效应后,在环向层应力未达到强度极限之前,筒肩部位的螺旋层就已经达到了经折减后的纤维拉伸强度,导致预测的爆破位置发生改变,爆破压力数值降低,更接近实验测试值。对于B气瓶,由于相对于A气瓶减少了一个±14°螺旋层,导致气瓶BOSS部位附近的螺旋层非常薄弱,成为爆破失效起始位置,增加的±90°环向层导致筒身冗余设计,因此气瓶爆破压力较小。对于两种分析方法,其预测的失效部位一致,均为BOSS区域,由于折减分析方法的螺旋层纤维强度进行了折减,因此其预测的爆破压力更低,误差更小。对于C气瓶,由于相对于A气瓶减少了一个±90°环向层,因此环向层的承载能力降低,而封头部位承载能力较强,气瓶在筒身段发生爆破。在两种分析方法中,其筒身段环向层的纤维拉伸强度相同,因此两种方法的预测结果一致。因此,本文提出的考虑纤维强度折减效应的IV型气瓶爆破失效分析,能更精准预测螺旋层主导的气瓶爆破压力和爆破形式,对于IV型气瓶的轻量化设计具有重要的指导意义。

5. 结 论

以提高气瓶分析精度为目的,本文进行了纤维强度折减效应研究,并发展了考虑纤维强度折减效应的IV型气瓶折减分析方法。得到以下结论:

(1)基于纤维缠绕结构平板和标准层合结构平板拉伸的实验和仿真对比,发现了缠绕结构纤维方向强度折减规律。随着缠绕角度和缠绕层厚度的增加,折减系数减小,纤维方向承载能力降低,使用线性拟合获得本文气瓶缠绕层纤维强度随缠绕角度和厚度变化的折减经验公式;

(2)开展了3种铺层气瓶的水压爆破试验,并与两种预测方法的预测结果进行对比。结果发现,折减分析方法较传统分析方法具有更高的爆破压力预测精度,对A铺层和B铺层气瓶的爆破压力预测误差分别从+8.18%和+15.42%降低至5.19%和+6.07%;

(3) 3种铺层的爆破失效位置预测结果中,折减分析方法较传统分析方法具有更高的预测准确度。采用纤维强度折减系数对Ⅳ型气瓶螺旋层纤维拉伸强度进行修正,可有效提升气瓶爆破失效行为分析结果的合理性。

-

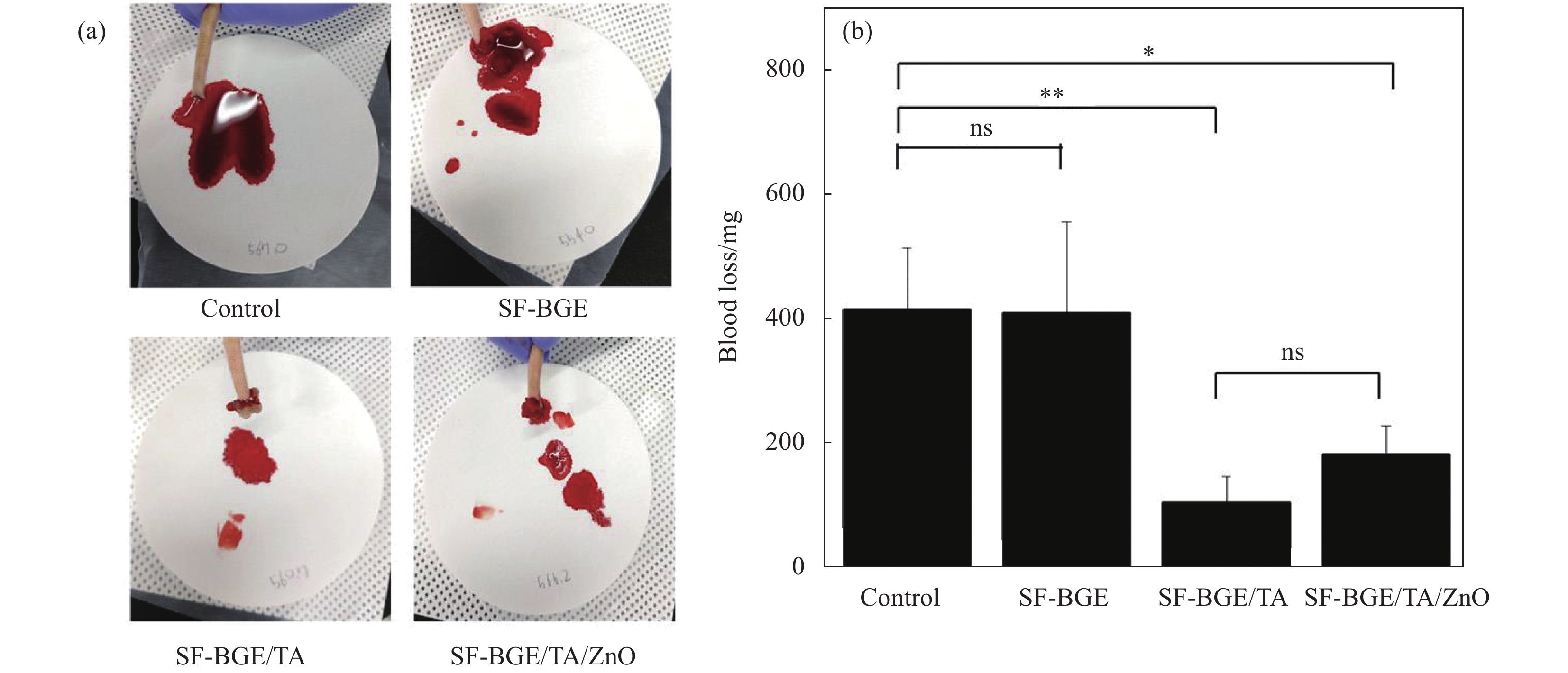

图 2 (a)截尾后给予改性后易溶于水的丝素蛋白(SF-BGE)、加入了单宁酸的易溶于水的丝素蛋白溶液(SFBGE/TA)和SF-BGE/TA/ZnO水凝胶后失血的照片;(b)对照组、SF-BGE、SF-BGE/TA、SF-BGE/TA、SF-BGE/TA/氧化锌水凝胶致伤大鼠的失血量(结果报告为平均值±标准差 (n=3);统计学处理采用单因素方差分析和Tukey's后置检验(*p<0.05,**p<0.01))[48]

Figure 2. (a) Photographs of blood loss after tail amputation and administration of SF-BGE, SFBGE/TA and SF-BGE/TA/ZnO hydrogel; (b) Blood loss from injury rat tail of control, SF-BGE, SF-BGE/TA, and SF-BGE/TA/ZnO hydrogel (The results are reported as the mean±standard deviation (n=3); Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01))[48]

SF—Silk fibroin; BGE—Butyl glycidyl ether; TA—Tannic acid; ns—No significance

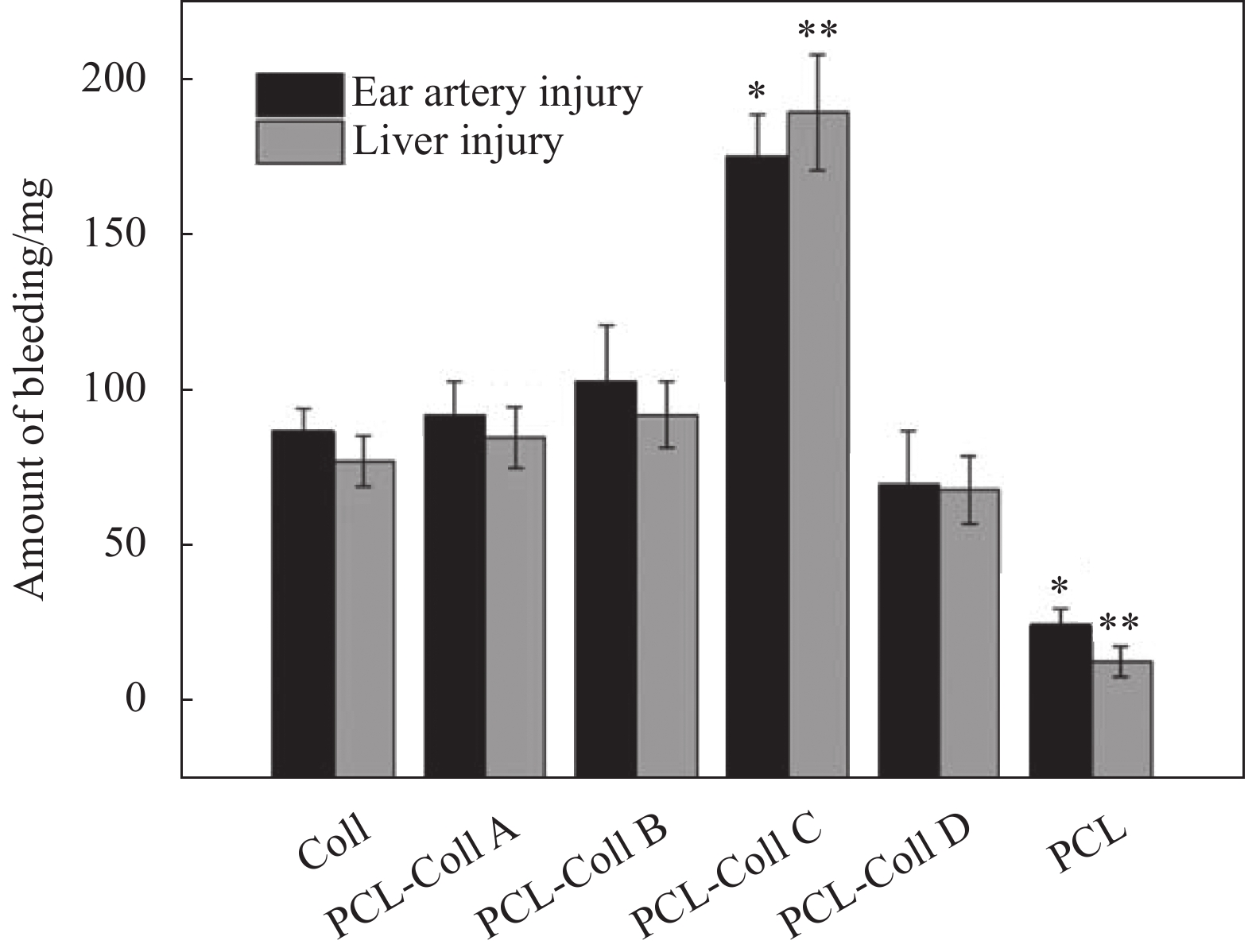

图 3 兔耳动脉和肝脏损伤模型中不同膜片的出血量(PCL-Coll (A~D)组与Coll组之间的统计学意义分别为*p<0.005,**p<0.05)[57]

Figure 3. The amount of bleeding of different films in injury models of rabbit ear artery and liver (Statistical significances between PCL-Coll (A-D) groups and ColI are denoted as *p<0.05, **p<0.005)[57]

PCL—Polycaprolactone

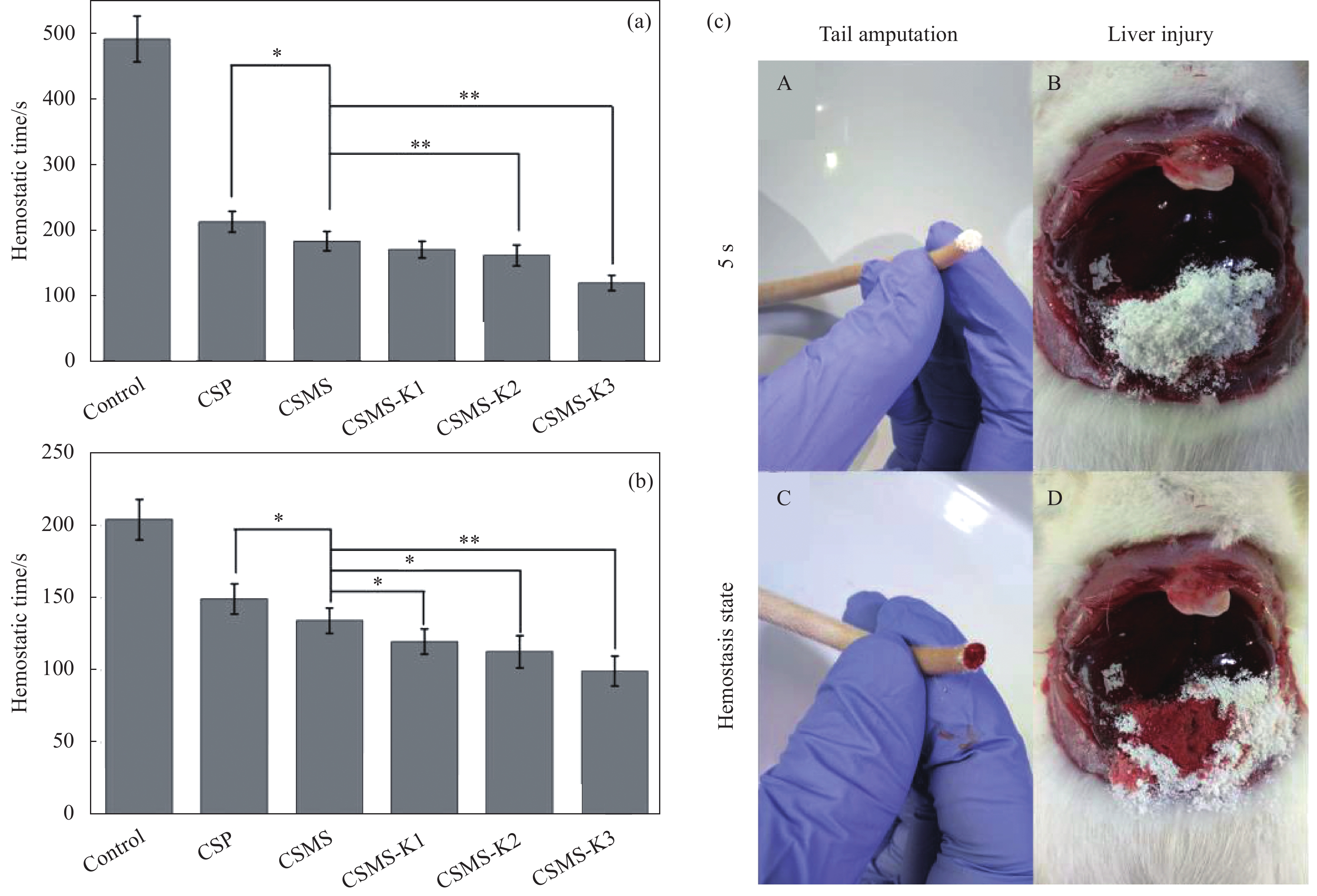

图 4 (a)大鼠断尾模型的止血时间;(b)大鼠肝撕裂伤模型止血时间;(c)大鼠断尾和肝撕裂模型的数字图像(将CSMS-K3涂于A尾部切割处和B肝撕裂伤处;涂抹CSMS-K3 5 min后C大鼠尾部切割处和D肝撕裂伤处;伤处形成暗红色血块,出血停止)[85]

Figure 4. (a) Hemostasis time in rat tail amputation model; (b) Hemostasis time in rat liver laceration model; (c) Digital images of rat tail amputation and liver laceration models (CSMS-K3 was applied onto A the tail cut and B on the liver injury; 5 min after application on the C rat tail cut and D the liver laceration; Dark-red blood clot was formed on the injured sites, bleeding stopped)[85]

CSP—Chitosan particles; CSMS—Chitosan porous microspheres; * indicates difference between the two groups of data and p<0.05; ** indicates significant difference and p<0.01

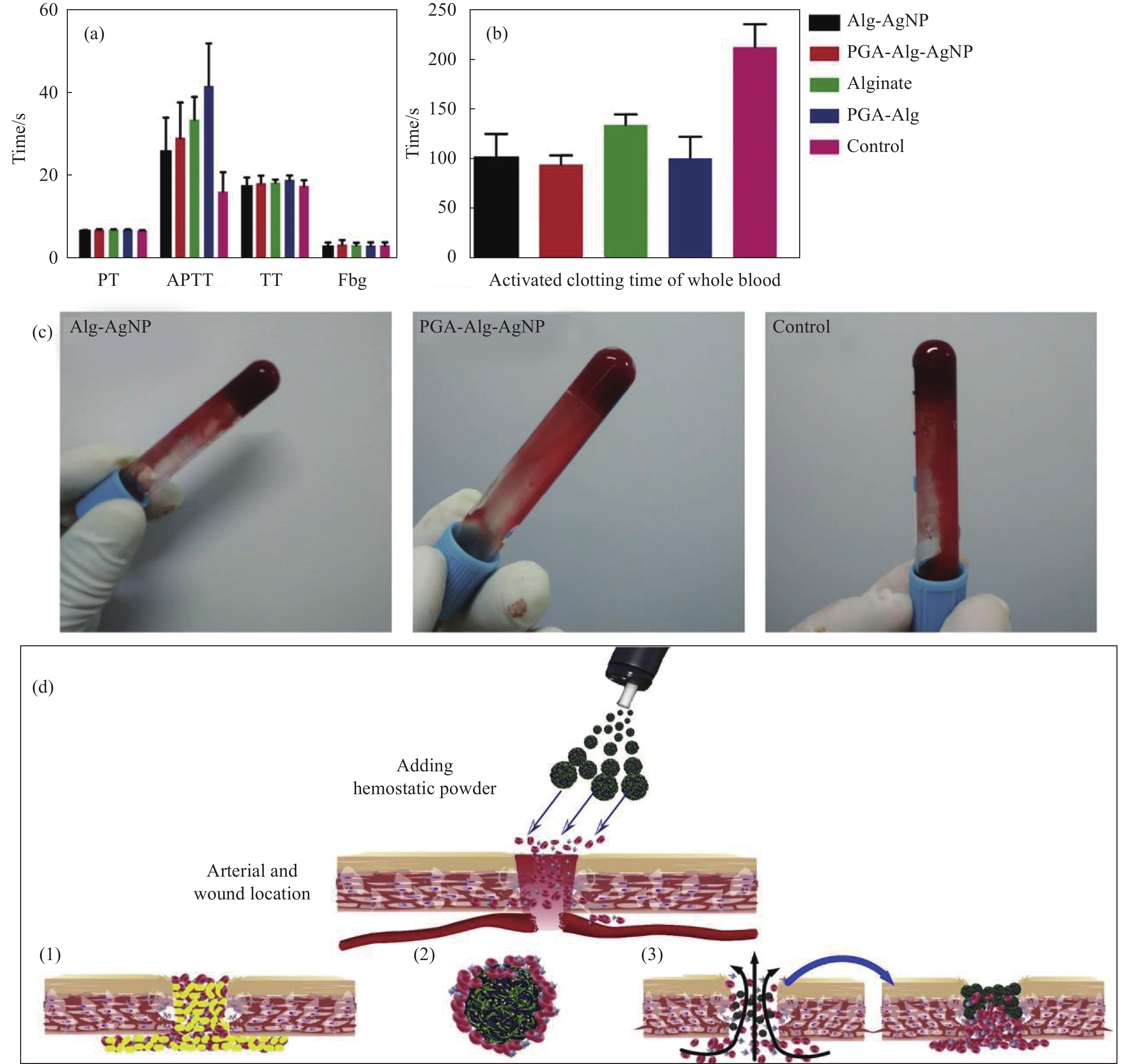

图 5 纯海藻酸微球、海藻酸/银纳米(Alg/AgNPs)、聚(γ-谷氨酸) (PGA)/Alg/AgNPs和PGA/Alg复合微球的止血分析:(a)血浆凝血性能;(b)凝血时间;(c)凝血图像;(d) PGA/Alg/AgNPs微球的止血示意图((1)止血剂提供外源性凝血成分,加速伤口血液凝结;(2)止血剂促进红细胞、凝血因子、血小板聚集,加速凝血;(3)止血剂吸收血液中水分,增加血细胞、血小板、凝血因子浓度,阻断创面,促进聚集止血[93])

Figure 5. Hemostasis assays of pure alginate microspheres, Alg/AgNPs, PGA/Alg/AgNPs, and PGA/Alg composite microspheres: (a) Blood plasma clotting performance; (b) Clotting blood time; (c) Coagulation images; (d) Schematic hemostasis of PGA/Alg/Ag NPs microspheres ((1) The hemostatic agent provides extrinsic coagulation components to accelerate blood clotting on the wound; (2) The hemostatic agent promotes the aggregation of red blood cells, coagulation factors and platelets, and accelerates the coagulation; (3) The hemostatic agent absorbs water in the blood, increases the concentration of blood cells, platelets, and coagulation factors, block the wound area and promotes the aggregation and hemostasis[93])

PT—Prothrombin time; APTT—Activated partial thromboplastin time; TT—Thrombin time; Fbg—Fibrinogen; PGA—Poly(γ-glutamic acid)

表 1 现有商品化生物质止血材料

Table 1 Existing commercial biomass hemostatic materials

Hemostatic material Product name Manufacturer Mechanism of hemostasis Hemostatic effect Limitations or deficiencies Ref. Fibrin sealant Tisseel;

Evicel;

Beriplast PBaxter;

Ethicon;

CSL BehringSimulates the coagulation process in the body and quickly forms blood clots Complete hemostasis was achieved within 30 s (Arterial bypass) to 6 min (Carotid endarterectomy) The price is expensive, and the cost of transportation and storage is high; It is contraindicated in patients with bovine allergies, who have adverse effects including rash, coagulation disorders, anaphylaxis, and death from premade antibodies [16-17] Oxidized cellulose Surgicel;

Cutanplast;

SurgicelJohnson;

B. Braun;

EthiconImmediately after the material encounters blood, the fluid in the blood is extracted and blood proteins, platelets, red blood cells and other active components are captured, resulting in an increased concentration of coagulation factors and an accelerated coagulation process Hemostasis is usually successful within 5 min (Open surgery) Foreign body reactions, minor postoperative complications, as foci of infection or anaphylaxis, manifested mainly by acute dermatitis, eczema, and serous tumors [9, 18] Gelatin sponges Gelfoam;

GelfoamPfizer;

BaxterAttaches to the bleeding site, allowing platelets to stay in uniform pores, activating the coagulation cascade Hemostasis was successfully achieved within 5 min (Reoperative cardiac surgery or emergency resternotomy) Inability to pack bleeding, and the possibility of breaking the clot when the sponge is removed; It may cause thrombosis of small blood vessels or an inflammatory reaction [17, 19] Microporous polysaccharides Arista AH Starch

MedicalIt concentrates blood solids by absorbing water and low-molecular-weight compounds from the blood, thereby providing hemostasis and providing a scaffold for the formation of fibrin clots Haemostasis was completed at 90 s (5 mm pork kidney incision) to 200 s (12 mm pork kidney incision) There will be a slight inflammatory reaction at the beginning of use [20-22] Chitosan sponge HemCon;

ChitoGauze PRO;

CeloxHemCon Medical Technologies;

HemCon Medical Technologies;

Z-MedicaPositively charged chitosan binds to negatively charged red blood cells. As a result, it leads to the formation of sticky clots to promote hemostasis Complete hemostasis usually occurs within 2 min (Tooth extraction surgery) For limb injuries, tourniquets are required [23-24] Notes: CSL—Commonwealth Serum Laboratories; AH—Absorbable hemostasis; PRO—Professional. 表 2 蛋白类止血材料的材料类型、体内模型和止血效果

Table 2 Material types, in vivo models, and hemostatic effects of protein-based hemostatic materials

Hemostatic

materialType of material Model of hemostasis Hemostatic effect Keratin Injectable hydrogel[34] Mouse model of liver injury Occlusion hemostasis was achieved in 90 s Nanoparticles[35] Rat model of liver injury and tail docking The hemostasis time was 60 s and 90 s Silk fibroin Composite sponge[47] Mouse model of liver injury 150 s to completely stop bleeding Nanocomposite hydrogels[48] Rat tail docking model The blood loss was only (183.4±50.1) mg Collagen Porous sponges[56] Rat tail docking model Complete hemostasis in 320 s Nanofiber membranes[57] Rabbit ear artery, liver injury model The hemostasis time was (95.34±10.05) s and

(67.05±7.15) sSelf-healing hydrogel[58] Mouse hemorrhagic liver model The blood loss was only (0.4±0.15) g 表 3 多糖类止血材料的材料类型、体内模型和止血效果

Table 3 Material types, in vivo models, and hemostatic effects of polysaccharide hemostatic materials

Hemostatic material Type of material Model of hemostasis Hemostatic effect Cellulose Composite sponge[67] Rat tail docking and liver injury model The blood loss was 159.46 mg and 80.44 mg Nanocomposite fibers[70] Lemonified human plasma, lemonified bovine whole blood The coagulation time was (143±19) s and (67±5) s Powder[83] Mouse tail docking model The hemostasis time was 158 s, and the blood loss was only 11.0 mg Chitosan Composite microspheres[85] A model of tail docking and liver laceration in rats The hemostasis time is 134 s and 99 s Composite hydrogel[86] Rat model of liver injury and femoral artery injury The hemostasis time was (53±3) s and (189±9) s Alginic acid Composite porous microspheres[91] Rat model of liver laceration and tail breakage The hemostasis time was (73±5) s and (134±5) s Foam[94] Porcine liver injury model The hemostasis time is 5 min Starch Superabsorbent

hydrogel[101]Rat model of femoral artery injury The hemostasis time <10 s Powder[103] Rabbit model of ear vein, dorsal, femoral artery, liver injury The hemostasis time was 52 s, 46 s, 122 s and 102 s Hyaluronic acid Drug-loaded microporous powder[105] Rabbit ear artery, liver injury model The hemostasis time is (108±5) s and (120±6) s Sponge[113] Mouse model of liver injury The hemostasis time was <60 s, and the blood loss was only 23.2 mg Cryogel[114] Rat model of liver injury The hemostasis time is 72 s -

[1] VOS T, LIM S S, ABBAFATI C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. The Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1204-1222. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

[2] BAYLIS J R, LEE M M, ST JOHN A E, et al. Topical tranexamic acid inhibits fibrinolysis more effectively when formulated with self-propelling particles[J]. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2019, 17(10): 1645-1654. DOI: 10.1111/jth.14526

[3] LIU C, LIU X, LIU C, et al. A highly efficient, in situ wet-adhesive dextran derivative sponge for rapid hemostasis[J]. Biomaterials, 2019, 205: 23-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.016

[4] HICKMAN D A, PAWLOWSKI C L, SEKHON U D S, et al. Biomaterials and advanced technologies for hemostatic management of bleeding[J]. Advanced Materials, 2018, 30(4): 1700859. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201700859

[5] HOLCOMB J B, STANSBURY L G, CHAMPION H R, et al. Understanding combat casualty care statistics[J]. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 2006, 60(2): 397-401. DOI: 10.1097/01.ta.0000203581.75241.f1

[6] ZHONG Y, HU H, MIN N, et al. Application and outlook of topical hemostatic materials: A narrative review[J]. Annals of Translational Medicine, 2021, 9(7): 577. DOI: 10.21037/atm-20-7160

[7] GIDAY S A, KIM Y, KRISHNAMURTY D M, et al. Long-term randomized controlled trial of a novel nanopowder hemostatic agent (TC-325) for control of severe arterial upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a porcine model[J]. Endoscopy, 2011, 43(4): 296-299. DOI: 10.1055/s-0030-1256125

[8] KATSUYAMA S, MIYAZAKI Y, KOBAYASHI S, et al. Novel, infection-free, advanced hemostatic material: Physical properties and preclinical efficacy[J]. Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies, 2020, 29(5): 283-292. DOI: 10.1080/13645706.2019.1627373

[9] ZHANG S, LI J, CHEN S, et al. Oxidized cellulose-based hemostatic materials[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2020, 230: 115585. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115585

[10] MONTAZERIAN H, DAVOODI E, BAIDYA A, et al. Engineered hemostatic biomaterials for sealing wounds[J]. Chemical Reviews, 2022, 122(15): 12864-12903. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c01015

[11] YANG X, LIU W, LI N, et al. Design and development of polysaccharide hemostatic materials and their hemostatic mechanism[J]. Biomaterials Science, 2017, 5(12): 2357-2368. DOI: 10.1039/C7BM00554G

[12] CHEN J, CHENG W, CHEN S, et al. Urushiol-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their self-assembly into a Janus membrane as a highly efficient hemostatic material[J]. Nanoscale, 2018, 10(48): 22818-22829. DOI: 10.1039/C8NR05882B

[13] OTROCKA-DOMAGALA I, JASTRZEBSKI P, ADAMIAK Z, et al. Safety of the long-term application of QuikClot Combat Gauze, ChitoGauze PRO and Celox Gauze in a femoral artery injury model in swine—A preliminary study[J]. Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 2016, 19(2): 337-343. DOI: 10.1515/pjvs-2016-0041

[14] SUN X, LI J, SHAO K, et al. A composite sponge based on alkylated chitosan and diatom-biosilica for rapid hemostasis[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2021, 182: 2097-2107. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.123

[15] YU L, ZHANG H, XIAO L, et al. A bio-inorganic hybrid hemostatic gauze for effective control of fatal emergency hemorrhage in "Platinum Ten Minutes"[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022, 14(19): 21814-21821.

[16] ALBALA D M. Fibrin sealants in clinical practice[J]. Cardiovascular Surgery, 2003, 11(Supplement 1): 5-11.

[17] HONG Y M, LOUGHLIN K R. The use of hemostatic agents and sealants in urology[J]. The Journal of Urology, 2006, 176(6): 2367-2374.

[18] AL-ATTAR N, DE JONGE E, KOCHARIAN R, et al. Safety and hemostatic effectiveness of SURGICEL® powder in mild and moderate intraoperative bleeding[J]. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis, 2023, 29: 10760296231190376.

[19] KTARI O, FRASSANITO P, GESSI M, et al. Gelfoam migration: A potential cause of recurrent hydrocephalus[J]. World Neurosurgery, 2020, 142: 212-217. DOI: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.214

[20] HUMPHREYS M R, LINGEMAN J E, TERRY C, et al. Renal injury and the application of polysaccharide hemospheres: A laparoscopic experimental model[J]. Journal of Endourology, 2008, 22(6): 1375-1381. DOI: 10.1089/end.2008.0008

[21] LYBARGER K S. Review of evidence supporting the Arista™ absorbable powder hemostat[J]. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research, 2024, 17: 173-188.

[22] ZHU J, WU Z, SUN W, et al. Hemostatic efficacy and biocompatibility evaluation of a novel absorbable porous starch hemostat[J]. Surgical Innovation, 2022, 29(3): 367-377. DOI: 10.1177/15533506211046100

[23] AZARGOON H, WILLIAMS B J, SOLOMON E S, et al. Assessment of hemostatic efficacy and osseous wound healing using HemCon dental dressing[J]. Journal of Endodontics, 2011, 37(6): 807-811. DOI: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.02.023

[24] WEDMORE I, MCMANUS J G, PUSATERI A E, et al. A special report on the chitosan-based hemostatic dressing: Experience in current combat operations[J]. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 2006, 60(3): 655-658. DOI: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199392.91772.44

[25] BURNETT L R, RAHMANY M B, RICHTER J R, et al. Hemostatic properties and the role of cell receptor recognition in human hair keratin protein hydrogels[J]. Biomaterials, 2013, 34(11): 2632-2640. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.022

[26] LUSIANA, REICHL S, MULLER-GOYMANN C C. Keratin film made of human hair as a nail plate model for studying drug permeation[J]. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 2011, 78(3): 432-440. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.01.022

[27] SHAVANDI A, SILVA T H, BEKHIT A A, et al. Keratin: Dissolution, extraction and biomedical application[J]. Biomaterials Science, 2017, 5(9): 1699-1735. DOI: 10.1039/C7BM00411G

[28] YAN R R, XUE D, SU C, et al. A keratin/chitosan sponge with excellent hemostatic performance for uncontrolled bleeding[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2022, 218: 112770. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112770

[29] YE W, QIN M, QIU R, et al. Keratin-based wound dressings: From waste to wealth[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2022, 211: 183-197. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.04.216

[30] FENG C C, LU W F, LIU Y C, et al. A hemostatic keratin/alginate hydrogel scaffold with methylene blue mediated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2022, 10(25): 4878-4888. DOI: 10.1039/D2TB00898J

[31] VERMA V, VERMA P, RAY P, et al. Preparation of scaffolds from human hair proteins for tissue-engineering applications[J]. Biomedical Materials, 2008, 3(2): 025007. DOI: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/2/025007

[32] ABOUSHWAREB T, EBERLI D, WARD C, et al. A keratin biomaterial gel hemostat derived from human hair: Evaluation in a rabbit model of lethal liver injury[J]. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 2009, 90(1): 45-54.

[33] RAHMANY M B, HANTGAN R R, VAN DYKE M. A mechanistic investigation of the effect of keratin-based hemostatic agents on coagulation[J]. Biomaterials, 2013, 34(10): 2492-2500. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.008

[34] TANG A, LI Y, YAO Y, et al. Injectable keratin hydrogels as hemostatic and wound dressing materials[J]. Biomaterials Science, 2021, 9(11): 4169-4177. DOI: 10.1039/D1BM00135C

[35] LUO T, HAO S, CHEN X, et al. Development and assessment of kerateine nanoparticles for use as a hemostatic agent[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2016, 63: 352-358. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.03.007

[36] HAGHNIAZ R, GANGRADE A, MONTAZERIAN H, et al. An all-in-one transient theranostic platform for intelligent management of hemorrhage[J]. Advanced Science, 2023, 10(24): e2301406. DOI: 10.1002/advs.202301406

[37] ZHU H, WU B, FENG X, et al. Preparation and characterization of bioactive mesoporous calcium silicate-silk fibroin composite films[J]. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 2011, 98(2): 330-341.

[38] SARAN K, SHI P, RANJAN S, et al. A moldable putty containing silk fibroin yolk shell particles for improved hemostasis and bone repair[J]. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2015, 4(3): 432-445. DOI: 10.1002/adhm.201400411

[39] WEI W, LIU J, PENG Z, et al. Gellable silk fibroin-polyethylene sponge for hemostasis[J]. Artificial Cells Nanomedicine and Biotechnology, 2020, 48(1): 28-36. DOI: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1699805

[40] GIL E S, PANILAITIS B, BELLAS E, et al. Functionalized silk biomaterials for wound healing[J]. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2013, 2(1): 206-217. DOI: 10.1002/adhm.201200192

[41] LI X, LI B, MA J, et al. Development of a silk fibroin/HTCC/PVA sponge for chronic wound dressing[J]. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers, 2014, 29(4): 398-411. DOI: 10.1177/0883911514537731

[42] QIAO Z, LYU X, HE S, et al. A mussel-inspired supramolecular hydrogel with robust tissue anchor for rapid hemostasis of arterial and visceral bleedings[J]. Bioactive Materials, 2021, 6(9): 2829-2840.

[43] SHEFA A A, TAZ M, LEE S Y, et al. Enhancement of hemostatic property of plant derived oxidized nanocellulose-silk fibroin based scaffolds by thrombin loading[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 208: 168-179. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.12.056

[44] LEI C, ZHU H, LI J, et al. Preparation and hemostatic property of low molecular weight silk fibroin[J]. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 2016, 27(5): 403-418. DOI: 10.1080/09205063.2015.1136918

[45] BARKUN A N, MOOSAVI S, MARTEL M. Topical hemostatic agents: A systematic review with particular emphasis on endoscopic application in GI bleeding[J]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2013, 77(5): 692-700. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.020

[46] HUANG X, FU Q, DENG Y, et al. Surface roughness of silk fibroin/alginate microspheres for rapid hemostasis in vitro and in vivo[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2021, 253: 117256. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117256

[47] LEE J, CHOI H N, CHA H J, et al. Microporous hemostatic sponge based on silk fibroin and starch with increased structural retentivity for contact activation of the coagulation cascade[J]. Biomacromolecules, 2023, 24(4): 1763-1773. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.2c01512

[48] YANG C M, LEE J, LEE S Y, et al. Silk fibroin/tannin/ZnO nanocomposite hydrogel with hemostatic activities[J]. Gels, 2022, 8(10): 650. DOI: 10.3390/gels8100650

[49] SUN L, LI B, SONG W, et al. Comprehensive assessment of Nile tilapia skin collagen sponges as hemostatic dressings[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2020, 109: 110532. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110532

[50] LIU X, ZHENG M, WANG X, et al. Biofabrication and characterization of collagens with different hierarchical architectures[J]. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 2019, 6(1): 739-748.

[51] JIANG X, WANG Y, FAN D, et al. A novel human-like collagen hemostatic sponge with uniform morphology, good biodegradability and biocompatibility[J]. Journal of Biomaterials Applications, 2017, 31(8): 1099-1107. DOI: 10.1177/0885328216687663

[52] WANG Q, CHEN J, WANG D, et al. Rapid hemostatic biomaterial from a natural bath sponge skeleton[J]. Marine Drugs, 2021, 19(4): 220. DOI: 10.3390/md19040220

[53] BROEKEMA F I, VAN OEVEREN W, BOERENDONK A, et al. Hemostatic action of polyurethane foam with 55% polyethylene glycol compared to collagen and gelatin[J]. Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering, 2016, 27(2-3): 149-159. DOI: 10.3233/BME-161578

[54] LUO J, MENG Y, ZHENG L, et al. Fabrication and characterization of Chinese giant salamander skin composite collagen sponge as a high-strength rapid hemostatic material[J]. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 2018, 30(4): 247-262.

[55] SHI X, FANG Q, DING M, et al. Microspheres of carboxymethyl chitosan, sodium alginate and collagen for a novel hemostatic in vitro study[J]. Journal of Biomaterials Applications, 2015, 30(7): 1092-1102.

[56] DAO M, CHENG X, SHAO Z, et al. Isolation, characterization and evaluation of collagen from jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum Kishinouye for use in hemostatic applications[J]. PLOS One, 2017, 12(1): e0169731. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169731

[57] CHENG W, ZHANG Z, XU R, et al. Incorporation of bacteriophages in polycaprolactone/collagen fibers for antibacterial hemostatic dual-function[J]. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 2018, 106(7): 2588-2595. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.b.34075

[58] DING C, TIAN M, FENG R, et al. Novel self-healing hydrogel with injectable, pH-responsive, strain-sensitive, promoting wound-healing, and hemostatic properties based on collagen and chitosan[J]. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 2020, 6(7): 3855-3867.

[59] CIDREIRA A C M, DE CASTRO K C, HATAMI T, et al. Cellulose nanocrystals-based materials as hemostatic agents for wound dressings: A review[J]. Biomedical Microdevices, 2021, 23(4): 43. DOI: 10.1007/s10544-021-00581-0

[60] FAN X, LI M, YANG Q, et al. Morphology-controllable cellulose/chitosan sponge for deep wound hemostasis with surfactant and pore-foaming agent[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2021, 118: 111408. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111408

[61] FAN X, LI Y, LI N, et al. Rapid hemostatic chitosan/cellulose composite sponge by alkali/urea method for massive haemorrhage[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 164: 2769-2778. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.312

[62] LAURENCE S, BAREILLE R, BAQUEY C, et al. Development of a resorbable macroporous cellulosic material used as hemostatic in an osseous environment[J]. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2005, 73A(4): 422-429. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.a.30280

[63] LI B, PAN W, SUN X, et al. Hemostatic effect and safety evaluation of oxidized regenerated cellulose in total knee arthroplasty—A randomized controlledtrial[J]. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2023, 24(1): 797. DOI: 10.1186/s12891-023-06932-7

[64] AYDEMIR SEZER U, SAHIN İ, ARU B, et al. Cytotoxicity, bactericidal and hemostatic evaluation of oxidized cellulose microparticles: Structure and oxidation degree approach[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 219: 87-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.05.005

[65] HERNÁNDEZ-BONILLA S, RODRÍGUEZ-GARCÍA A M, JIMÉNEZ-HEFFERNAN J A, et al. FNA cytology of postoperative pseudotumoral lesions induced by oxidized cellulose hemostatic agents[J]. Cancer Cytopathology, 2019, 127(12): 765-770. DOI: 10.1002/cncy.22194

[66] VELÁZQUEZ-AVIÑA J, MÖNKEMÜLLER K, SAKAI P, et al. Hemostatic effect of oxidized regenerated cellulose in an experimental gastric mucosal resection model[J]. Endoscopy, 2014, 46(10): 878-882. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1365494

[67] BIAN J, BAO L, GAO X, et al. Bacteria-engineered porous sponge for hemostasis and vascularization[J]. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 2022, 20(1): 47. DOI: 10.1186/s12951-022-01254-7

[68] OHTA S, NISHIYAMA T, SAKODA M, et al. Development of carboxymethyl cellulose nonwoven sheet as a novel hemostatic agent[J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2015, 119(6): 718-723. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.10.026

[69] LIU R, DAI L, SI C, et al. Antibacterial and hemostatic hydrogel via nanocomposite from cellulose nanofibers[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2018, 195: 63-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.085

[70] UDANGAWA R N, MIKAEL P E, MANCINELLI C, et al. Novel cellulose—Halloysite hemostatic nanocomposite fibers with a dramatic reduction in human plasma coagulation time[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2019, 11(17): 15447-15456.

[71] WU Z, ZHOU W, DENG W, et al. Antibacterial and hemostatic thiol-modified chitosan-immobilized AgNPs composite sponges[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2020, 12(18): 20307-20320.

[72] RADWAN-PRAGŁOWSKA J, PIĄTKOWSKI M, DEINEKA V, et al. Chitosan-based bioactive hemostatic agents with antibacterial properties—Synthesis and characterization[J]. Molecules, 2019, 24(14): 2629.

[73] LAN G, LU B, WANG T, et al. Chitosan/gelatin composite sponge is an absorbable surgical hemostatic agent[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2015, 136: 1026-1034. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.10.039

[74] GHEORGHIȚĂ D, MOLDOVAN H, ROBU A, et al. Chitosan-based biomaterials for hemostatic applications: A review of recent advances[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(13): 10540. DOI: 10.3390/ijms241310540

[75] HU Z, ZHANG D Y, LU S T, et al. Chitosan-based composite materials for prospective hemostatic applications[J]. Marine Drugs, 2018, 16(8): 273. DOI: 10.3390/md16080273

[76] YAN T, CHENG F, WEI X, et al. Biodegradable collagen sponge reinforced with chitosan/calcium pyrophosphate nanoflowers for rapid hemostasis[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2017, 170: 271-280. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.080

[77] DOWLING M B, KUMAR R, KEIBLER M A, et al. A self-assembling hydrophobically modified chitosan capable of reversible hemostatic action[J]. Biomaterials, 2011, 32(13): 3351-3357. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.033

[78] KUMAR A, VIMAL A, KUMAR A. Why chitosan? From properties to perspective of mucosal drug delivery[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2016, 91: 615-622. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.054

[79] BELLICH B, D'AGOSTINO I, SEMERARO S, et al. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" of chitosans[J]. Marine Drugs, 2016, 14(5): 99. DOI: 10.3390/md14050099

[80] KHAN M A, MUJAHID M. A review on recent advances in chitosan based composite for hemostatic dressings[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 124: 138-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.045

[81] LORD M S, CHENG B, MCCARTHY S J, et al. The modulation of platelet adhesion and activation by chitosan through plasma and extracellular matrix proteins[J]. Biomaterials, 2011, 32(28): 6655-6662. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.062

[82] FISCHER T, THATTE H, NICHOLS T, et al. Synergistic platelet integrin signaling and factor XII activation in polyacetyl glucosamine fiber-mediated hemostasis[J]. Biomaterials, 2005, 26(27): 5433-5443.

[83] WU S, HUANG Z, YUE J, et al. The efficient hemostatic effect of Antarctic krill chitosan is related to its hydration property[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 132: 295-303. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.030

[84] LI B, WANG J, GUI Q, et al. Continuous production of uniform chitosan beads as hemostatic dressings by a facile flow injection method[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2020, 8(35): 7941-7946. DOI: 10.1039/D0TB01462A

[85] SUN X, TANG Z, PAN M, et al. Chitosan/kaolin composite porous microspheres with high hemostatic efficacy[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2017, 177: 135-143. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.131

[86] SUNDARAM M N, AMIRTHALINGAM S, MONY U, et al. Injectable chitosan-nano bioglass composite hemostatic hydrogel for effective bleeding control[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 129: 936-943. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.220

[87] ZHENG Y, PAN N, LIU Y, et al. Novel porous chitosan/N-halamine structure with efficient antibacterial and hemostatic properties[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2021, 253: 117205. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117205

[88] LEE K Y, MOONEY D J. Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications[J]. Progress in Polymer Science, 2012, 37(1): 106-126. DOI: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.06.003

[89] CHEN Y, WU L, LI P, et al. Polysaccharide based hemostatic strategy for ultrarapid hemostasis[J]. Macromolecular Bioscience, 2020, 20(4): e1900370. DOI: 10.1002/mabi.201900370

[90] ALAVI M, RAI M. Recent progress in nanoformulations of silver nanoparticles with cellulose, chitosan, and alginic acid biopolymers for antibacterial applications[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2019, 103(21-22): 8669-8676. DOI: 10.1007/s00253-019-10126-4

[91] PAN M, TANG Z, TU J, et al. Porous chitosan microspheres containing zinc ion for enhanced thrombosis and hemostasis[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2018, 85: 27-36. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.12.015

[92] ZHONG W. Efficacy and toxicity of antibacterial agents used in wound dressings[J]. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology, 2015, 34(1): 61-67. DOI: 10.3109/15569527.2014.890939

[93] TONG Z, YANG J, LIN L, et al. In situ synthesis of poly(γ- glutamic acid)/alginate/AgNP composite microspheres with antibacterial and hemostatic properties[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 221: 21-28. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.05.035

[94] CHOUDHARY H, RUDY M B, DOWLING M B, et al. Foams with enhanced rheology for stopping bleeding[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2021, 13(12): 13958-13967.

[95] ZHENG Y, SHARIATI K, GHOVVATI M, et al. Hemostatic patch with ultra-strengthened mechanical properties for efficient adhesion to wet surfaces[J]. Biomaterials, 2023, 301: 122240. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122240

[96] YANG X, LIU W, XI G, et al. Fabricating antimicrobial peptide-immobilized starch sponges for hemorrhage control and antibacterial treatment[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 222: 115012.

[97] CHEN J, CHEN S, CHENG W, et al. Fabrication of porous starch microspheres by electrostatic spray and supercritical CO2 and its hemostatic performance[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 123: 1-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.219

[98] PAVLOVIC S, BRANDAO P R G. Adsorption of starch, amylose, amylopectin and glucose monomer and their effect on the flotation of hematite and quartz[J]. Minerals Engineering, 2003, 16(11): 1117-1122. DOI: 10.1016/j.mineng.2003.06.011

[99] LIU G, GU Z, HONG Y, et al. Electrospun starch nanofibers: Recent advances, challenges, and strategies for potential pharmaceutical applications[J]. Journal of Controlled Release, 2017, 252: 95-107. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.016

[100] CHEN F, CAO X, YU J, et al. Quaternary ammonium groups modified starch microspheres for instant hemorrhage control[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2017, 159: 937-944. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.08.024

[101] MIRZAKHANIAN Z, FAGHIHI K, BARATI A, et al. Synthesis and characterization of fast-swelling porous superabsorbent hydrogel based on starch as a hemostatic agent[J]. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 2015, 26(18): 1439-1451. DOI: 10.1080/09205063.2015.1100496

[102] AWASTHI G P, ADHIKARI S P, KO S, et al. Facile synthesis of ZnO flowers modified graphene like MoS2 sheets for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity and antibacterial properties[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2016, 682: 208-215. DOI: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.04.267

[103] HOU Y, XIA Y, PAN Y, et al. Influences of mesoporous zinc-calcium silicate on water absorption, degradability, antibacterial efficacy, hemostatic performances and cell viability to microporous starch based hemostat[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2017, 76: 340-349. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.094

[104] QIAN J, CHEN Y, YANG H, et al. Preparation and characterization of crosslinked porous starch hemostatic[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 160: 429-436. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.189

[105] SU H, WEI S, CHEN F, et al. Tranexamic acid-loaded starch hemostatic microspheres[J]. RSC Advances, 2019, 9(11): 6245-6253. DOI: 10.1039/C8RA06662K

[106] CUI R, CHEN F, ZHAO Y, et al. A novel injectable starch-based tissue adhesive for hemostasis[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2020, 8(36): 8282-8293. DOI: 10.1039/D0TB01562H

[107] SU Y, CHEN H, LIU Q, et al. Thermoresponsive gels with embedded starch microspheres for optimized antibacterial and hemostatic properties[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2024, 16(10): 12321-12331.

[108] MASTERS K S, SHAH D N, LEINWAND L A, et al. Crosslinked hyaluronan scaffolds as a biologically active carrier for valvular interstitial cells[J]. Biomaterials, 2005, 26(15): 2517-2525. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.018

[109] YAMANLAR S, SANT S, BOUDOU T, et al. Surface functionalization of hyaluronic acid hydrogels by polyelectrolyte multilayer films[J]. Biomaterials, 2011, 32(24): 5590-5599. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.030

[110] WANG Y, LIU G, WU L, et al. Rational design of porous starch/hyaluronic acid composites for hemostasis[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 158: 1319-1329. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.018

[111] ABALLAY A, HERMANS M H E. Neodermis formation in full thickness wounds using an esterified hyaluronic acid matrix[J]. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 2019, 40(5): 585-589. DOI: 10.1093/jbcr/irz057

[112] ROEHRS H, STOCCO J G, POTT F, et al. Dressings and topical agents containing hyaluronic acid for chronic wound healing[J]. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023, 7(7): Cd012215.

[113] LIU J Y, LI Y, HU Y, et al. Hemostatic porous sponges of cross-linked hyaluronic acid/cationized dextran by one self-foaming process[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2018, 83: 160-168. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.10.007

[114] WANG M, HU J, OU Y, et al. Shape-recoverable hyaluronic acid-waterborne polyurethane hybrid cryogel accelerates hemostasis and wound healing[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022, 14(15): 17093-17108.

[115] CHEN Z, YE S Y, YANG Y, et al. A review on charred traditional Chinese herbs: Carbonization to yield a haemostatic effect[J]. Pharmaceutical Biology, 2019, 57(1): 498-506. DOI: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1645700

[116] DONG X, LIANG W, MEZIANI M J, et al. Carbon dots as potent antimicrobial agents[J]. Theranostics, 2020, 10(2): 671-686. DOI: 10.7150/thno.39863

[117] LI D, XU K Y, ZHAO W P, et al. Chinese medicinal herb-derived carbon dots for common diseases: Efficacies and potential mechanisms[J]. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2022, 13: 815479.

[118] SZCZEPANKOWSKA J, KHACHATRYAN G, KHACHATRYAN K, et al. Carbon dots—Types, obtaining and application in biotechnology and food technology[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(19): 14984.

[119] VILLALBA-RODRÍGUEZ A M, GONZÁLEZ-GONZÁLEZ R B, MARTÍNEZ-RUIZ M, et al. Chitosan-based carbon dots with applied aspects: New frontiers of international interest in a material of marine origin[J]. Marine Drugs, 2022, 20(12): 782. DOI: 10.3390/md20120782

[120] KRYSTYJAN M, KHACHATRYAN G, KHACHATRYAN K, et al. Polysaccharides composite materials as carbon nanoparticles carrier[J]. Polymers, 2022, 14(5): 948. DOI: 10.3390/polym14050948

[121] YAN X, ZHAO Y, LUO J, et al. Hemostatic bioactivity of novel pollen typhae carbonisata-derived carbon quantum dots[J]. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 2017, 15(1): 60. DOI: 10.1186/s12951-017-0296-z

[122] LI S, GUO Z, ZHANG Y, et al. Blood compatibility evaluations of fluorescent carbon dots[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2015, 7(34): 19153-19162.

[123] HAN B, SHEN L, XIE H, et al. Synthesis of carbon dots with hemostatic effects using traditional Chinese medicine as a biomass carbon source[J]. ACS Omega, 2023, 8(3): 3176-3183. DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.2c06600

[124] WU T, LI M, LI T, et al. Natural biomass-derived carbon dots as a potent solubilizer with high biocompatibility and enhanced antioxidant activity[J]. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2023, 10: 1284599. DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1284599

[125] ZHANG J, ZOU L, LI Q, et al. Carbon dots derived from traditional Chinese medicines with bioactivities: A rising star in clinical treatment[J]. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 2023, 6(10): 3984-4001. DOI: 10.1021/acsabm.3c00462

[126] SUN Z, LU F, CHENG J, et al. Haemostatic bioactivity of novel Schizonepetae Spica Carbonisata-derived carbon dots via platelet counts elevation[J]. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology, 2018, 46(sup3): 308-317. DOI: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1492419

[127] LIU X, WANG Y, YAN X, et al. Novel Phellodendri Cortex (Huang Bo)-derived carbon dots and their hemostatic effect[J]. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine, 2018, 13(4): 391-405.

[128] ZHANG M, CHENG J, LUO J, et al. Protective effects of Scutellariae Radix Carbonisata-derived carbon dots on blood-heat and hemorrhage rats[J]. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2023, 14: 1118550. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1118550

[129] ALTINTIG E, SARICI B, KARATAŞ S. Prepared activated carbon from hazelnut shell where coated nanocomposite with Ag+ used for antibacterial and adsorption properties[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022, 30(5): 13671-13687. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-022-23004-w

[130] CHENG P, XUE X, SU J, et al. 1H NMR-based metabonomic revealed protective effect of Moutan Cortex charcoal on blood-heat and hemorrhage rats[J]. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2019, 169: 151-158. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.02.044

[131] ZHANG Y, GE X L, ZHANG J, et al. Effect of the oxygenic groups on activated carbon on its hemocompatibility[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2024, 233: 113655. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113655

[132] WANG S, ZHANG Y, SHI Y, et al. Rhubarb charcoal-crosslinked chitosan/silk fibroin sponge scaffold with efficient hemostasis, inflammation, and angiogenesis for promoting diabetic wound healing[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2023, 253(Pt 2): 126796.

-

目的

全世界每年约有6000万人遭受严重创伤,其中约200万人因为受创后无法控制的严重出血而死亡,意外创伤造成的严重出血的黄金急救时间只有几分钟。因此,伤口的快速止血和愈合对于解决意外事故造成的出血具有重要意义。本文以止血材料的生物质来源为依托,探索生物质止血材料的种类、制备方法与止血性能之间的相关性,同时关注其在具体应用中的止血效果。

方法利用生物质材料在临床止血领域的发展现状为依托,采用分类法来探究不同生物质原材料及制备方法对止血材料的止血性能和生物相容性的影响,并分析其相应的止血应用效果,即从止血时间和失血量来分析其止血效果。

结果依据原材料来源的不同,生物质止血材料主要可分为以下几种:(1)蛋白类止血材料,包括角蛋白类、丝素蛋白类和胶原蛋白类;(2)多糖类止血材料,包括纤维素类、壳聚糖类、海藻酸类、淀粉类和透明质酸类;(3)其他生物质止血材料,包括中药类碳点和中药类活性炭。以角蛋白、丝素蛋白、胶原蛋白为代表的蛋白类和以纤维素、壳聚糖、海藻酸为代表的多糖类等生物质材料,因其无毒性、低抗原性、良好的生物相容性、生物可降解性等优点在止血领域展现了前所未有的应用价值。同时,复合生物质止血材料能够综合各种生物质材料的优点,具备更好的止血效果和生物相容性。

结论生物质止血材料相比其他止血材料具有独特的天然优势,如角蛋白类止血材料能够促使纤维蛋白原聚合成纤维蛋白,加速凝血;丝素蛋白类止血材料能够促进成纤维细胞增殖、再上皮化和胶原合成,以此促进伤口的止血和愈合;胶原蛋白类止血材料的抗原性低;纤维素类止血材料具备优异的机械性能和可再生性;壳聚糖类止血材料表面的阳离子簇可以与红细胞上的阴离子相互作用,诱导血小板聚集,实现止血;海藻酸类止血材料具有优异的吸水性和生物降解性;淀粉类止血材料和透明质酸类止血材料具有优异的生物相容性和可降解性。但无论哪一类生物质止血材料都很难实现完美止血性、高抗菌性及低毒和低抗原性的并存,复合生物质止血材料必然是未来的发展趋势。此外,新型生物质止血材料的开发必需综合考虑各种生物质材料的物理性质、化学性质和生理学性质,以赋予其优异的止血性、低毒性、低抗原性、抗菌性和生物相容性等综合性能。

下载:

下载: